Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Curious Toys by Elizabeth Hand

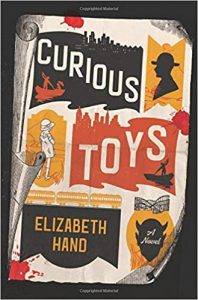

Curious Toys, Elizabeth Hand (Mulholland 978-0-316-48588-3, $27.00, 384pp, hc) October 2019.

Curious Toys, Elizabeth Hand (Mulholland 978-0-316-48588-3, $27.00, 384pp, hc) October 2019.

Like her darkly wonderful Cass Neary crime novels, Elizabeth Hand’s Curious Toys is what we here at Locus Genre Control refer to as “associational,” meaning it’s not materially SF or fantasy, but contains much of interest to genre readers – and not solely because of Hand’s distinguished career in these parts. Curious Toys is being marketed largely as a historical mystery or crime novel, placing it vaguely in the company of the sort of SF-adjacent cryptohistories we occasionally get from Caleb Carr, E.L. Doctorow, and others – not quite secret histories, not quite alternate histories, but not quite not, either. In the case of Curious Toys, the major speculative element involves the Chicago outsider artist and writer Henry Darger, whose voluminously obsessive decades of work, discovered only as he was dying in 1973, have already inspired poems by John Ashbery, a song by Natalie Merchant, and a film by Jessica Yu, among other things. So in one sense, Hand’s novel is about an unknown episode in the early life of a fantasy artist and writer, although I’m not sure if anyone has actually read the 15,000 page illustrated Story of the Vivian Girls (that’s only a small part of the title), and if anyone has, I hope they’re okay. Darger’s title, however, is crucial to Hand’s perfectly modulated drop-kick ending, and could make a case for reading Curious Toys as a secret history of a very mysterious psyche.

Those who have followed Darger’s legendary posthumous career tend to think of him as the sad and incredibly lonely old recluse who survived a Dickensian childhood to spend more than a half-century filling his room with manuscripts, paintings, and collages, but Hand introduces us to a Darger in 1915, still in his early twenties, clearly disturbed in unknowable ways and already obsessed with the 1911 disappearance and murder of a real-life five-year-old girl named Elsie Paroubek. Vaguely thinking to protect other children, Darger haunts Riverview Park, a famous but rather tacky amusement park which actually survived in Chicago until 1967. There he meets the novel’s main viewpoint character, a 14-year-old girl named Pin, whose mother works as a fortune-teller at the park and who disguises herself as a boy partly to enable her to more easily run errands – which at times involve delivering drugs to Essanay Studios, a film company whose stars and writers included Charlie Chaplin, Wallace Beery, and Louella Parsons. Pin’s best friend there is a girl her own age named Glory (whose actual identity is something of a late reveal), and her developing crush on Glory introduces a theme of gender fluidity that also comes to resonate with some of the odder aspects of Darger’s own art. (A few other figures from Chicago history also get walk-ons, notably Ben Hecht as an ambitious reporter, long before his renowned Hollywood career.)

When a young girl is seen entering the park’s ominously named Hell Gate ride with an older man – but not emerging with him – Pin and Darger are the only witnesses, and Pin’s later discovery of the girl’s body sets off a murder investigation that initially focuses unfairly on one of the park’s few black employees, introducing a theme of bigotry also reflected in the period’s attitudes toward Roma and Italians. Pin is especially disturbed because of her sister’s disappearance a few years earlier, and for Darger it recalls the Paroubek case and his own fantasy of running a child-protective society with his only friend Willhie. Hand carefully inserts a few chapters from the chilling point of view of the actual murderer, a figure worthy of Thomas Harris, whose creepy obsessions with dolls and little girls’ clothes are more than enough to give the novel overtones of a horror story. Hand’s research into Chicago history is impeccable without ever seeming gratuitous, and even secondary characters such as Chaplin and Hecht emerge as fascinating and complex. But the story – which tightens its spiral as neatly as any murder mystery – finally belongs to Pin and Darger, and mostly to Pin, an absolutely marvelous creation who, in the superb ending, turns out to be far more than we expected.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the October 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.