Rabbit, Run: Arley Sorg and Josh Pearce Discuss Us

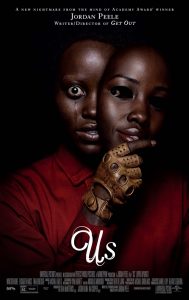

From Jordan Peele, writer and director of Get Out, comes Us — a new horror film following Adelaide Wilson (Lupita Nyong’o), her husband Gabe (Winston Duke), and their two children Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) and Jason (Evan Alex) as the family vacations in Santa Cruz CA, where something terrible had happened to Adelaide as a child.

From Jordan Peele, writer and director of Get Out, comes Us — a new horror film following Adelaide Wilson (Lupita Nyong’o), her husband Gabe (Winston Duke), and their two children Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) and Jason (Evan Alex) as the family vacations in Santa Cruz CA, where something terrible had happened to Adelaide as a child.

Josh: That’s probably all we can say about the plot without giving too much away.

Arley: We’ll do spoilers in a separate section at the end.

Josh: Okay, well then. I thought it was scarier than Get Out.

Arley: I thought it was about the same — not scary at all, but I think that everyone has a different scary barometer. There are scenes I recognize as being scary to other people. It’s definitely a horror movie and has a lot of really lovely creepy visuals and creepy moments and it ratchets up the violence from Get Out.

Josh: I didn’t think there was a specific scary moment — not a lot of jump scares, etc. — but there were a lot of times where the suspenseful music would build but nothing would happen. Or the wife would be looking out the window and there’s no one there. Or the husband is so blissfully unaware that you keep expecting something to happen to him. It’s like hearing an unresolved chord progression and getting an itch in your ears. Finish the progression! Finish what you’re saying! Resolve this tension somehow.

The directing deserves particular attention here, not only for the cinematography but also for the way that Peele uses the language of film itself to evoke classic horror movies and set expectations for the audience: VHS tapes of C.H.U.D. and The Goonies are visible in the opening shot; Jason wears a Jaws t-shirt while several beach and boat scenes directly mirror that film; and twin characters look as though they’ve stepped right out of The Shining. Us knows how to build on those foundations and provide a little tongue-in-cheek horror comedy. Like Get Out, there is a lot of social commentary, but also a bit of campy goofiness.

Most obviously, scenes on the beach boardwalk draw direct reference to Lost Boys, especially when, in a scene set in 1986, Adelaide’s mother says, “They’re shooting a movie over there by the carousel.”

Josh: I like that it was set local to us. Santa Cruz hasn’t been done very often in movies.

Arley: It’s not San Francisco, which has been done to death. And that area has lots of shadows and lonely places. The way the opening scene on the boardwalk was shot, the way Adelaide (played as a child by Madison Curry) would look at someone, and the camera would tilt and pan, I could feel her disconnectedness. You get the sense that she’s completely different from everyone she saw, that her life is different; and her parents were physically distant and distracted. That was one of my favorite parts of the movie, without words. It was such an amazing encapsulation of isolation and otherness.

Josh: And that scene takes on a completely different meaning later in the movie.

Also noteworthy were the performances from the four main actors, each of whom portrayed multiple roles, and completely sold it. The differences in makeup, body language, and vocalizations all added up to transform each actor into two completely different people, and at no point during the film is that illusion broken. Not only were the individual performances fantastic, but the four of them together formed a family unit that became a fifth character of its own. Their interaction with each other was positive but not over the top. The banter back and forth was believable and entertaining.

Us presents interesting gender roles; both of Lupita Nyong’o’s characters are strong women. All of the characters have their own moments, but she’s the hero of the movie, the driving force of most of the action, making the big decisions. In one scene where Gabe, after failing to make a series of rational choices, tries to say, “This is what we’re going to do,” Adelaide cuts in with, “You don’t get to decide anymore!” (This mirrors Winston Duke’s own line as M’Baku in Black Panther, saying to the colonizer CIA officer: “You cannot speak here.”)

Gabe’s masculinity is shown not as a super-tough guy but as a normal dad who gets his bat, is scared to go outside, drops his voice when confronting the intruders, then comes back inside and says, “Let’s call the police.” (Which Adelaide had already demanded.) Making him a real person, rather than a stereotype, is an important choice.

Josh: Always comparing himself to Josh (Tim Heidecker). Josh has a bigger boat. Josh has a backup generator.

Arley: When you’re a Black person on the edge of white society, you’re always comparing yourself. They won’t accept me unless I have what they have, unless I do certain things, behave a certain way. Okay, here’s where I get racial. My thought when I first saw them was, “Those four are really dark.” Which is relevant. Many people don’t know, but in many Black communities it’s a thing, being lighter skinned or having certain kind of hair or a certain nose. So when I saw a family of four dark, dark-skinned people, I knew that was a deliberate choice, and a bold one. Hollywood usually casts light-skinned Black people in lead roles. This was a great choice and in doing so kind of revealed to people the beauty and capability of everybody, and that these notions of dark skin versus light skin are stupid. It gave them visibility. I saw that some people on Twitter said, why does it matter about race, and I think if you’re not POC it’s easy to say “I don’t care about race, I just want to see a movie.” If you are a POC it’s good to see a depiction of yourself, you need to see yourself from time to time. For Black people what’s needed are characters who are not just rappers or comic relief. And it’s not just the Black community with these notions of dark skin versus light skin: it’s Asian, Indian, and so on. Different cultures have different historic reasons for it.

Josh: Now let’s do spoilers.

SPOILERS from here on out:

The story builds slowly from an unsettling beginning. There are clues for meticulously observant viewers — the opening text and the VHS tapes are only the most obvious. There are a number of surprises, but for people who watch a lot of movies or read a lot of books, the direction of the narrative will become apparent. Certain storytelling choices are obvious, but that doesn’t detract from its enjoyability. The movie hints at the underground for most of the movie, but once Jason gets abducted, it can only follow that Adelaide will pursue him into the tunnels, and that is when and where everything will be revealed.

The audience is assured of at least some answers, because this is a Jordan Peele movie. It might be a weird explanation, but it’s still an explanation, perfectly fitting in with his recent Twilight Zone involvement and his past Twilight Zone influences. Us has a science fiction reasoning to it. Pulp science fiction, but still science fiction, if one ignores the talk about souls and the real possibility of rabbit starvation.

Arley: I remember Hands Across America, which was such a surreal thing. It was cool that he tapped into it. It gave the movie a certain vibe and context.

Josh: Once I realized that the family wasn’t going to die, the tension became “How are they going to get out of this?” rather than “How is everyone going to die?” or “Is everyone going to die?” which are more commonly how horror movies go. And the family each deals with their doubles in their own ways, each according to their means.

Arley: I think there’s also a subtler underlying commentary on class structure. People underground, deprived, less privileged. Adelaide’s shadow says, “We haven’t seen a sky.” Get Out was more racial, and this is more class-based. But my very first thought, at the opening scene, was: because this is Jordan Peele, are we reading into it when it’s supposed to be just a fun horror movie?

Josh: No. He’s doing all this on purpose. He makes deliberate decisions. C.H.U.D. is about homeless people. Hands Across America was about homeless people. This is class and wealth and privilege commentary. The part in the movie that made me say, “OH,” was when the white family said, “Ophelia, turn up the lights.” They were literally living safe in a glass bubble, telling their robot assistant to take care of things for them, disbelieving that they could come to harm. Completely different reaction from Adelaide’s family where Zora said, “There’s a family in our driveway,” and everyone immediately said, “Call the police.” Ophelia stood out to me because I used to work at a smart home company and I know this shit’s expensive. It’s all early adopter, wasteful rich, self-indulgent people buying this. Normal people don’t buy this.

Arley: Yeah. The lines, “Who are you people?” “We are Americans!” I cracked up. But it’s a straight out punch in your face: hey, you, living in the safety of your vacation, your nice clothes, your beautiful family, you are living here on the backs of people you won’t acknowledge. There’s also a cool reversal of typical horror movies in which the Black people are the wild party ones or the comedic relief, or, of course, the ones to get killed. In this one, the white family is drinking on the beach. Adelaide is the voice of reason because she turns down drinks and says we don’t need a boat. Ironically saying, we don’t need to be clones.

Josh: Agree. I got a total sense of clone hood from the white couple because they’re drinking, partying, got this vacation house, very shallow, very materialistic mentality. No one’s raising their kids, so their kids are assholes. And twins, which are genetically clones. I read the “We are Americans” line as meaning that America is the source of horrors, historically and currently.

Arley: The best thing about this movie is what happens after you’ve seen it. I think it’s a movie that should be seen with friends, family. Thinking about the movie afterwards, the conversations you have with people about it. It’s kind of amazing. The way it provokes thought and the way it provokes conversation. Like the rabbits. I think the rabbits represented loss of individuality and loss of freedom. That shot starts zoomed in on one rabbit then pulls out to show a bunch of identical rabbits, and they’re all in cages.

Josh: Yes. Very symbolic. Zora’s sweater said thỏ (“rabbit” in Vietnamese). It’s an Alice in Wonderland reference, going down the rabbit hole, so be prepared for some weird shit.

Arley: The only things that disappointed me were when the dad was fighting his doppelganger in the boat — I needed him to not do the things that he did. Unrealistic behaviors for those situations. Or that scene where Jason gets kidnapped. Neither of the parents, nor the sister, were watching him and he just gets snatched.

Josh: I agree. It’s an apocalypse, do you know where your children are? It had to happen, but we didn’t like the way it happened.

Arley: Final thought: Adelaide’s shadow says, “We have to make a statement that the world will see.” This is a metaphor for Black cinema. It’s important for people to vote with their money. This movie obviously broke records, which will shake up Hollywood, but whenever movies come out that are doing something different and important, chances are better that more movies like them will happen if you spend money on it. Black Panther, Captain Marvel, Us — these prove that diverse voices have an audience.

Written and directed by: Jordan Peele

Starring: Lupita Nyong’o, Winston Duke, Elisabeth Moss, Tim Heidecker, Shahadi Wright Joseph, Evan Alex, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Anna Diop, Cali Sheldon, Noelle Sheldon, Madison Curry, Ashley Mckoy, Napiera Groves, Lon Gowan & Alan Frazier

JOSH PEARCE, Assistant Editor, started working at Locus in 2016. He studied creative writing at SFSU and has sold short stories and poems to a variety of speculative fiction magazines. Born and raised in the Bay Area, he currently lives in the East Bay with his wife and son and spends way too much time on Twitter: @fictionaljosh. One time, Ken Jennings signed his chest.

ARLEY SORG, Associate Editor, grew up in England, Hawaii, and Colorado. He studied Asian Religions at Pitzer College. He lives in Oakland, and usually writes in local coffee shops. A 2014 Odyssey Writing Workshop graduate, he is soldering together a novel, has thrown a few short stories into orbit, and hopes to launch more.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.