John Langan Reviews Clark Ashton Smith: The Emperor of Dreams

With H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith is one of the major writers associated with the original incarnation of Weird Tales magazine. Of the three, Lovecraft has received the lion’s share of critical attention, from the essays regularly published first in Lovecraft Studies and now the Lovecraft Annual, to such book-length studies as Maurice Levy’s Lovecraft: A Study in the Fantastic and Robert Waugh’s The Monster in the Mirror, to S.T. Joshi’s massive, exhaustive biography, I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H.P. Lovecraft. In addition, he’s been the subject of a number of film projects, from The Case of Howard Phillips Lovecraft to Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown. Although he and his work have not been recipients of the same extended study, Robert E. Howard’s fiction has been discussed in essays published in the periodical, The Dark Man, as well as two critical anthologies edited by Don Herron, and his life was the subject of a well-received film, The Whole Wide World (itself based on a memoir of Howard written by Novalyne Price Ellis). While praised by writers including Harlan Ellison and Fritz Leiber, Clark Ashton Smith has not been subject to the same degree of critical attention as his fellows. A number of notable essays on his fiction and poetry appeared in the late, lamented Studies in Weird Fiction, and Scott Connors has edited a fine selection of critical responses to his work (2006’s The Freedom of Fantastic Things), but in comparison to that lavished on Howard and especially Lovecraft, attention to Clark Ashton Smith lags behind.

With H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith is one of the major writers associated with the original incarnation of Weird Tales magazine. Of the three, Lovecraft has received the lion’s share of critical attention, from the essays regularly published first in Lovecraft Studies and now the Lovecraft Annual, to such book-length studies as Maurice Levy’s Lovecraft: A Study in the Fantastic and Robert Waugh’s The Monster in the Mirror, to S.T. Joshi’s massive, exhaustive biography, I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H.P. Lovecraft. In addition, he’s been the subject of a number of film projects, from The Case of Howard Phillips Lovecraft to Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown. Although he and his work have not been recipients of the same extended study, Robert E. Howard’s fiction has been discussed in essays published in the periodical, The Dark Man, as well as two critical anthologies edited by Don Herron, and his life was the subject of a well-received film, The Whole Wide World (itself based on a memoir of Howard written by Novalyne Price Ellis). While praised by writers including Harlan Ellison and Fritz Leiber, Clark Ashton Smith has not been subject to the same degree of critical attention as his fellows. A number of notable essays on his fiction and poetry appeared in the late, lamented Studies in Weird Fiction, and Scott Connors has edited a fine selection of critical responses to his work (2006’s The Freedom of Fantastic Things), but in comparison to that lavished on Howard and especially Lovecraft, attention to Clark Ashton Smith lags behind.

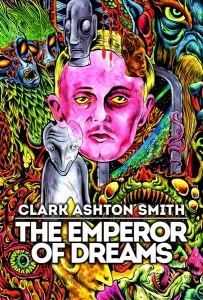

With his documentary, Clark Ashton Smith: The Emperor of Dreams, writer-director Darin Coehlo Spring looks to improve this situation. The poet, Donald Sidney Fryer, who knew Smith when he was a young man, is our guide to Smith’s life, a role in which he’s assisted by a cast of scholars, writers, and visual artists which includes the late Harlan Ellison, Scott Connors, Cody Goodfellow, S.T. Joshi, Wilum Pugmire, and the artist Skinner. Together, these figures take us through Smith’s biography and work in roughly chronological order.

In many ways, his life was a modest affair. He was born and lived the majority of his life in Auburn, California, now a decent-sized town, in Smith’s early years a settlement of approximately one thousand people. Through a combination of archival imagery and contemporary footage, the movie gives a good sense of just how rural, how remote a place Auburn was at the turn of the last century. Following primary school, Smith opted not to continue on to high school, feeling he could better educate himself at the local library, an assessment with which his parents agreed. As the film observes, he was thus an autodidact in much the same way as Lovecraft (and Howard, for that matter).

His early efforts writing poetry led Smith to contact with the contemporary poet George Sterling. An important influence on Smith, Sterling championed the younger man’s work and was responsible for exposing Smith to Baudelaire’s poetry, which would become another important source for his work. Despite having been considered a significant American poet during his lifetime, associated with a group of California-based writers including Ambrose Bierce and Jack London, Sterling has been largely forgotten by contemporary literary and cultural studies, overshadowed at this point by his former protégé. The documentary helps to restore some sense of Sterling’s significance, and in so doing fits Smith into a larger historical context. The culmination of this phase of Smith’s writing was his 1920 blank verse poem, The Hashish Easter, or The Apocalypse of Evil. A self-taught artist, Smith created an extensive set of illustrations to accompany the poem which have never been published alongside it, and it’s one of the accomplishments of the movie to show a generous selection of his art as selections from The Hashish Eater are being read. (It arouses hope that a print edition of the poem combining pictures and text might yet be published.)

The film proceeds to a discussion of Smith’s fiction, moving as it does so away from his relationship with Sterling to his developing epistolary friendship with H.P. Lovecraft. This coincided with the start of his career as a published fiction writer, pretty much all of which occurred before Lovecraft’s death in 1937. (Smith had written novels as a youth, but they remained unpublished until well after his death.) In part, the reason for Smith’s turn to prose was practical: he needed money in order to look after his aging parents. At the same time, his stories were not divorced from the material of his poetry; rather, they were a new way of approaching the same concerns. As it’s for his fiction that Smith has remained best known, this section of the documentary is in many ways its heart. Many of Smith’s stories were set in one of several invented locales: the prehistoric Hyperborea and Poseidonis, the imaginary medieval France of Averoigne, and the far future Zothique. Often driven by complex impulses, the characters in these stories brought a more complicated psychology into the pages of the pulp magazines in which they were published. The playful letters Smith and Lovecraft exchanged led to an equally playful sharing of elements from one another’s stories; though the film makes it clear that Smith was not Lovecraft’s disciple. Rather, he was an artistic equal engaged in exploring his own concerns through occasionally shared material. The high point of this portion of the documentary is a recreation of the circumstances under which Smith was inspired to create one of his signature stories, “The City of the Singing Flame,” in the staging of which the historical narrative collapses into that of the story. It’s a clever visual way to signal the connection between Smith’s extravagant narrative and his lived experience. From this same segment of the film emerges one of the interesting insights into Smith’s fiction, namely, its repeated focus on characters who pursue a goal that is simultaneously promises to fulfill their desires and to result in their destruction.

With the deaths of first his mother and then his father, not to mention Lovecraft (and Robert E. Howard, though the film does not treat Smith’s correspondence and friendship with him), Smith’s fiction writing came to end, the combined losses of his parents and friends having dried up that part of his creativity. Now the focus of his artistic activity shifted to carving local rock samples, a hobby for years that became the primary output for his aesthetic impulses. He would benefit from the foundation of Arkham House Press, which would collect his work in hardcover form for a new generation of readers, but while he received visits from younger writers such as Fritz Leiber, as well as the occasional fan who sought him out, the most significant event of his later years was his marriage to a younger woman with three teenaged children. Although it sounds like the plot for a particularly off-kilter sitcom, the marriage provided Smith with stability during the end of his life, and one of his stepsons would become his literary executor.

The film concludes with an excerpt from a recording of Smith reading, and it’s a fitting conclusion to the documentary, a reminder that his distinctive voice continues to speak to us down through the decades. With this movie, Darin Spring has filled in the outlines of Clark Ashton Smith’s life and person, in the process offering a fine introduction to the work of the man whose most famous poem demands the reader bow down to him, as he is the emperor of dreams. It’s quite the boast, but as fans of Smith’s work know, it’s one that’s hard to dispute.

Written and directed by: Darin Coelho Spring

John Langan is the author of two novels, The Fisherman (2016) and House of Windows (Night Shade 2009), and two collections of stories, The Wide Carnivorous Sky and Other Monstrous Geographies (2013) and Mr. Gaunt and Other Uneasy Encounters (2008). With Paul Tremblay, he co-edited Creatures: Thirty Years of Monsters (2011). One of the founders of the Shirley Jackson Awards, he served as a juror for its first three years. He lives in New York’s Mid-Hudson Valley with his wife and younger son.

This review and more like it in the January 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.