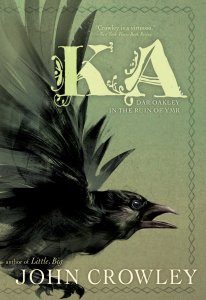

Faren Miller Reviews Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruin of Ymr by John Crowley

Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruin of Ymr, John Crowley (Simon & Schuster/Saga Press 978-1-4814-9559-2, $28.99, 444pp, hc) October 2017. Cover by Sonia Chagetzbanian.

John Crowley’s Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruin of Ymr sets the lead character between his two realms and hints at the wrecked planet of the frame story. In Dar’s iconic parlance, Ka is the life and mindset of Crows, Ymr the world that People inhabit and perceive. The prologue invokes post-apocalyptic SF in scenes as bleak as dark myths: the “great mountain at the end of the world” is an enormous heap of garbage (scavengers: People and Crows) in a chaotic future where plants no longer heed the seasons, species have vanished, and diseases range unchecked. The narrator’s wife died of one illness. A few years later, when Dar Oakley turns up in his backyard as “an obviously very sick Crow,” they learn to communicate and form a bond – the latest in Dar’s long series of friendships with individual humans.

John Crowley’s Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruin of Ymr sets the lead character between his two realms and hints at the wrecked planet of the frame story. In Dar’s iconic parlance, Ka is the life and mindset of Crows, Ymr the world that People inhabit and perceive. The prologue invokes post-apocalyptic SF in scenes as bleak as dark myths: the “great mountain at the end of the world” is an enormous heap of garbage (scavengers: People and Crows) in a chaotic future where plants no longer heed the seasons, species have vanished, and diseases range unchecked. The narrator’s wife died of one illness. A few years later, when Dar Oakley turns up in his backyard as “an obviously very sick Crow,” they learn to communicate and form a bond – the latest in Dar’s long series of friendships with individual humans.

Part one, “Dar Oakley in the Coming of Ymr”, goes deep into the past for Dar’s first encounter with prehistoric breakaways from a larger tribe, who build their own encampment and take a new identity as the Lake People. Intrigued by these intruders, a young and nameless Crow hangs around long enough to pick up some of their language, find a friend in the girl he knows as Fox Cap, and take the name she gives him – though he trims down the overwrought surname to “Oakley.” (While there’s plenty of satire in the book’s rich mix, this isn’t just a punning alter ego for Crowley.) When Fox Cap abruptly vanishes, Dar pursues her into a surreal place that stands apart from both their living realms, but is crucial for People. It lurks beyond every Part, linked to their changing notions of the Afterlife much as we link Crow and Raven to the dark abstraction Death. In Part 1 it’s known as the Happy Valley – which resembles Faerie, with unnerving twists on time for returning travelers.

Although this Crow’s fascination with Ymr makes him an oddball outsider (while giving him some understanding of Death and the Soul as humans regard them), he’s an unabashed carrion-eater. An early scene of tribal warfare reveals the wealth raptors can take from Battle, another concept that looms large throughout the book, as he flies over “the greatest bounty that any band of eaters of dead flesh had ever seen”: corpses strewn across a battlefield. Near the end of Part 1 he finds another food source when an old man he’s known fondly for years gets a “sky burial”: laid out as a feast for Crows. To them, the aged body is a multi-course banquet.

Part two, “Dar Oakley and the Saints”, brings the reborn protagonist into the company of monks (in a Christian monastery on the western shore of Europe), surveys another Battle scene, depicts a miracle with offhand nonchalance, then sends him questing with a Brother as his companion – to an afterlife like Dante’s Purgatory, from its Dark Wood to the bat-winged monsters torturing dead sinners. Though only a few souls from this medieval culture are destined for Heaven, several designated Saints ironically resemble friends from Dar’s previous life.

Part three, “Dar Oakley in the New World”, covers a lot more territory in its four chapters, roughly 150 pages. His lives as a New World Crow (a different species) play out along a timeline that extends from the era of the tribes, through the dire consequences of European discovery, on to the Civil War, and then the dawn of an industrial age where humans target Nature for continual attacks. Chapter One thrusts him into the dreamy/impish realm of the Beast Fable, where a bustling multi-creature society lies just beyond human reach. Nonetheless, many tribes have totem animals – most notably the People who call themselves Crows and make him their living emblem, as the narrative glides from fable toward history. In Chapter Two, the proud warriors of battling tribes yield before the onslaught of colonists and plagues.

The most striking tale in the next chapter, dominated by the Civil War, boldly reimagines Emily Dickinson as poet, war widow, and quietly “sensitive” mystic Anna Kuhn, one of the narrator’s ancestors. (The brief stanzas credited to her are so convincing, I had to double-check my hefty old edition of the Complete Poems to make sure that Crowley wrote them.) This alternate Emily helps strip away needless holiness from the exalted image reader-worshippers have given her: the virgin clad in white, martyred to illness before she could live out a full lifespan. Anna Kuhn bears children, wears black after her husband dies, and forms a bond with Dar Oakley in her old age.

I’ll end here, in hope that you’ll continue to explore this remarkable book on your own. You won’t regret it.

Faren C. Miller, Contributing Editor, worked full-time for Locus from 1981 to 2000, when she pulled up stakes and moved to Prescott, Arizona (a “mile-high city” not as widely known as that one in Colorado) with the man she subsequently married, Kerry Hanscom. She continues to review SF, fantasy, and horror — enjoying, analyzing, then forgetting all the details on a regular basis — and hopes to keep doing it for many years to come. Author of one fantasy, The Illusionists (Warner 1991), she is working on another which she’s confident will be finished before the next millennium rolls around.

This review and more like it in the November 2017 issue of Locus.