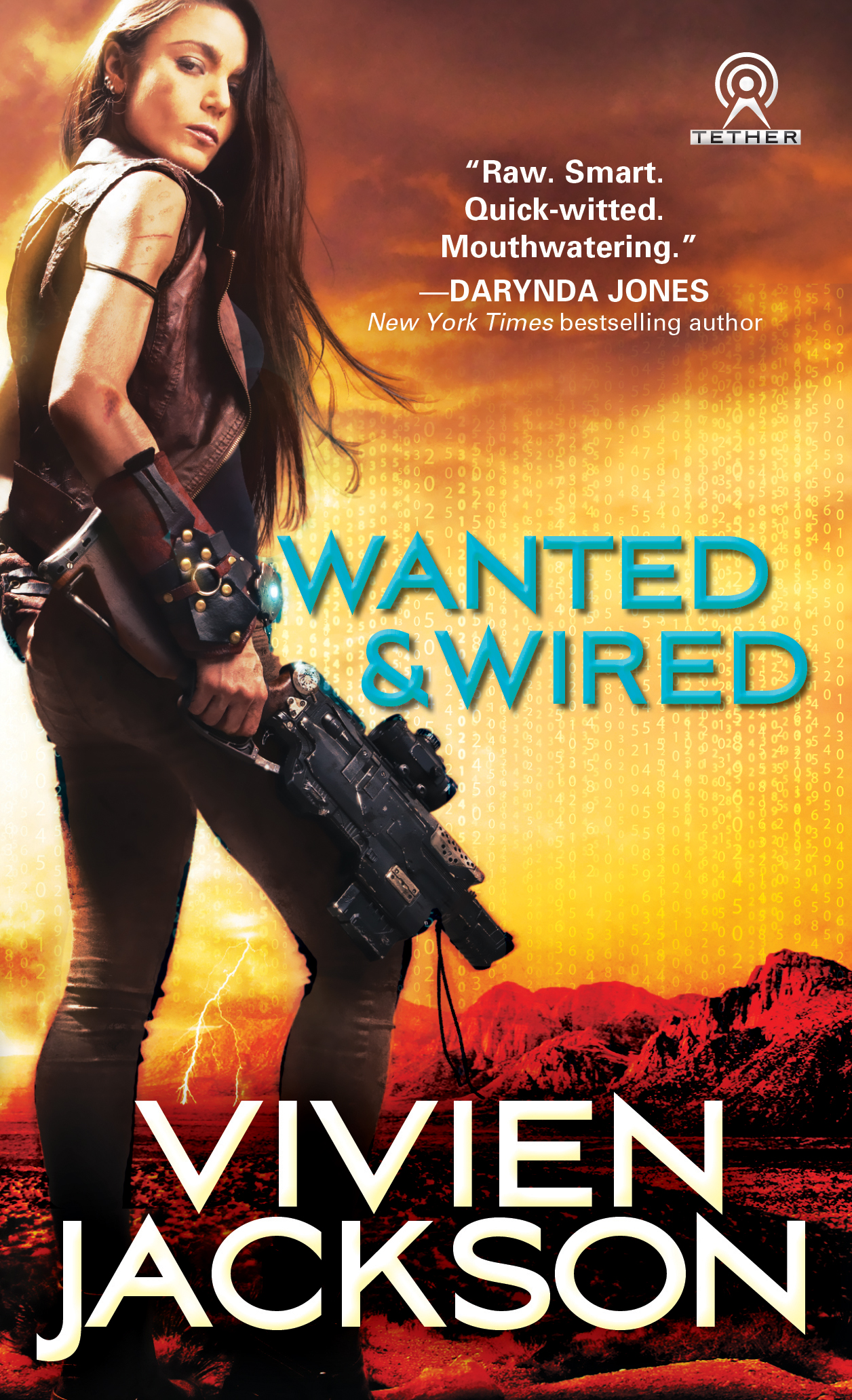

Vivien Jackson Guest Post–“Cybernetic Humans”

My brother is one of those guys who has a joke for every situation, so when he texted me an x-ray of a human shoulder that wasn’t fully connected, I texted back a question mark and a couple of confused emojis. Looking for the punchline, right? He replied with, “Oops,” followed by the observation that it is difficult to perform basic hygiene tasks, or really to do anything, after you’ve fallen fifteen feet onto concrete and obliterated a major joint.

Wait. Brother did what?

Oh yes, the clumsy is strong in our family. At any rate, he texted back that he had a scheduled surgery date whereupon he would be fitted with a super fancy German-manufactured titanium shoulder, complete with bolts and brackets and whirring bits.

“So basically, I’m gonna be the six million dollar man!” he said.

Crickets.

I neglected to mention that this brother is fifteen years older than me, didn’t I? So. After he explained what a six million dollar man was, I called him up and said, “Dude! You’re gonna be a cyborg! That is so cool!”

See, my formative years were crammed with technologically awesome characters who were both more and less than human—the “more machine now than man” Darth Vader, Roy Batty, the terminator who looked like Arnold Schwarzenegger, the terminator who looked like silver mucous, the sometimes decapitated and fluid-leaking androids in the Alien films, and, of course, RoboCop. Such an education made cyborgs as a concept fit neatly into my personal universe.

Now, I know some of you are thinking, wait, those examples weren’t all folks you’d want to look up to or idolize. Some of them were villains. Monsters. How are monsters cool and why do you want your brother to become one? But I counter with, they weren’t all bad. Plus, badness is relative. And while I admit it is always possible that luddite-infiltrated media and pop culture were trying to scare my generation away from newfangled technology by shoving the uncanny valley right into our faces at every opportunity, in the end they kind of failed.

See, I don’t think of cyborgs as scary. I think of them as illuminating.

Which is why I write about them now that I’m all grown up.

One question I start every cyborg-related story with is, what is it about tech alteration that both fascinates and frightens us? What is the benefit/sacrifice ratio?

I suspect that any comprehensive answer to these questions has something to do with our need to meta-metaphor ourselves. That is, we like to talk about, and think about, ourselves. A lot. Because cybernetic human characters can replace select and discrete bits of their humanity and focus in on the replaced part—or the missing part—they are fantastic metaphors for the human condition.

Before I go any further, I should clarify what I mean by cybernetic humans. We use a lot of terms to describe altered human-like organisms—cyborgs, transhumans, post-humans, androids, clones, ‘droids, avatars. But you’ve seen my list of childhood heroes/villains, so you already know I squash all those terms together into one mega-metaphor, which I call a cyborg but which may or may not have both organic and inorganic parts. Theodore Sturgeon’s human gestalt from More Than Human would qualify under my squashed-up definition because the pieces are isolable. So would Sophia, the purely inorganic robot who just gained citizenship in Saudi Arabia. (How creeptastically awesome is she!)

Combining the definitions into one term is not simply lazy—I mean, in one sense, yes, it’s horribly lazy and I’m so guilty and judge if you must—but what it does also is to shift the focus away from gadgetry like cyber eyes and wired reflexes and toward the intrinsic otherness. Because that’s what frightens and fascinates us: the otherness. The part that is almost like us but not quite. The part that mirrors our own struggle and gives us hope, or despair.

For my brother, the benefit of becoming other is a shoulder that works and doesn’t hurt. The sacrifice is the pain of injury, surgery, and convalescence. (A story about survival.)

For my character Heron, the benefit of becoming other is a brain that can interface with machines. The sacrifice is allowing himself to be regarded as subhuman by people whose admiration he covets. (A story about exclusion.)

For Roy Batty, the benefit of being other is the life experiences he has collected and relates so poetically. The sacrifice is that those memories are transient, temporary, “tears in the rain.” (A story about legacy, and maybe immortality.)

In an interview with Forbes magazine in 2016, Nobel Laureate Shimon Peres said something interesting about the man/machine future: “A man is greater than a robot. Instead of trying to make a better robot, try to make a better man.”

Except, see, I think we already have. Creatives have. By conceptualizing our human condition in a ready-made cybernetic metaphor, we have made a better man. A better us. And we can dissect the cyborg’s merits and flaws individually, without all the messy context and baggage that humans haul along.

The benefit to having created the cybernetic other is that we can see our strengths and flaws in brilliant detail. The sacrifice is that we then must look in a mirror and see only ourselves.

(A story about humans.)

Vivien Jackson is still waiting for her Hogwarts letter. Don’t you laugh. In the meantime, she writes, mostly fantastical or futuristic or kissing-related stories. When she isn’t writing, she’s performing a sacred duty nurturing the next generation of Whovian Browncoat Sindarin Jedi gamers, and their little dogs too. She has a degree in English, which only means she’s read gobs of stuff in that language. With her similarly geeky partner, she lives in Austin, Texas and watches a lot of football. She loves to hear from readers: www.vivienjackson.com.

Vivien Jackson is still waiting for her Hogwarts letter. Don’t you laugh. In the meantime, she writes, mostly fantastical or futuristic or kissing-related stories. When she isn’t writing, she’s performing a sacred duty nurturing the next generation of Whovian Browncoat Sindarin Jedi gamers, and their little dogs too. She has a degree in English, which only means she’s read gobs of stuff in that language. With her similarly geeky partner, she lives in Austin, Texas and watches a lot of football. She loves to hear from readers: www.vivienjackson.com.