Paul Di Filippo reviews Paolo Bacigalupi

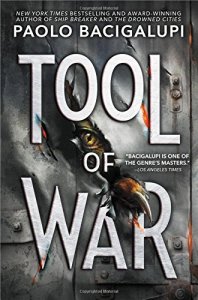

Tool of War, by Paolo Bacigalupi (Little, Brown 978-0-316-22083-5, $17.99, 384pp, hardcover) October 2017

The famously hazy interzone between fiction for adults and fiction for youths totally inverts, evaporates, resubstantiates, and turns into a four-dimensional labyrinth when we consider a novel such as Paolo Bacigalupi’s Tool of War. Demarcations and prohibitions and expectations become meaningless or double-valued, and in the end all one can say is that, no matter the marketing label, one is enjoying some masterful storytelling pitched to all age levels from adolescent on up.

The famously hazy interzone between fiction for adults and fiction for youths totally inverts, evaporates, resubstantiates, and turns into a four-dimensional labyrinth when we consider a novel such as Paolo Bacigalupi’s Tool of War. Demarcations and prohibitions and expectations become meaningless or double-valued, and in the end all one can say is that, no matter the marketing label, one is enjoying some masterful storytelling pitched to all age levels from adolescent on up.

This latest book is the third in what ISFDB labels the Ship Breaker series, after the title of the first volume from 2010. It’s set on our post-catastrophe Earth of indeterminate year, where dystopia has definitely arrived, but is not evenly distributed.

The first novel focused on the inhabitants of a scavengers’ settlement, Bright Sands Beach, situated on the Gulf Coast of the fallen-apart USA. Here, global corporations beach their useless oil tankers and cargo ships, and the desperate residents tear them apart by hand and primitive tools, selling the stripped components at meager rates via greedy middlemen back to other conglomerates in this scarcity economy. Naturally, such a life is brutal and short and empty of many pleasures or luxuries. Occasionally someone will find a bunker full of discarded petroleum, claim it, and become relatively rich. But such an event features odds worse than any lottery.

Our hero in this scenario is a young lad named Nailer, who knows no other way of life. Beset by an abusive father, he nonetheless labors with dexterity and cleverness. Unbeknownst to him, he is about to have a life-changing experience. A hurricane brings ashore a crashed luxury vessel, onboard which is a rich heiress named Nita. Nailer conceives of reuniting her with her family for a fabulous reward. But many factions, including his father, stand between him and his dreams.

Bacigalupi’s unrelentingly bleak, steamingly physical, mercilessly kinetic, all-too-likely future is no feel-good anti-dystopia where youthful hearts and pluck and naiveté win through. By the novel’s end, no global conditions have changed, and the reader realizes that the planet and its citizens, guilty and innocent alike, are doomed to labor onward under these burdens and make the best of things. And yet the individual victories and perils attain all the more weight due to the unrelenting hardness of life. There’s really no preachiness about how we citizens of 2017 are responsible for all these horrors, nor about the vast inequalities of the future, but rather a kind of realpolitik acceptance of life as she is lived, an agreement not to dwell on the unchangeable past, of working with what one is presented with and making the best of things. Also, all liberal and conservative pieties have been burned away in the chaos.

Nailer receives help in his quest from a chimera, a gene-spliced war creature named Tool, part-human, part-animal, and all killer. In an interview appended to the second book, The Drowned Cities, Bacigalupi reveals that he tried to continue the story of Nailer directly, but could not find a satisfying path. And so now Tool comes to the forefront of the new narrative, along with a fresh human protagonist named Mahlia. Tool is first seen on the run and nearly dead. Mahlia is an orphan and refugee who has found a niche as a physician’s assistant. It’s all rudimentary bush-doctoring however. Her path intersects with Tool’s, and she is instrumental in saving the life of the beast man. Together they will plunge into the half-aquatic, sprawling ruined infrastructure known as the Drowned Cities, where rival armies comprised of child soldiers and pitiless acquisitive adult leaders wage endless guerilla wars. At the end of this tale, Mahlia has attained some stability and even minor wealth, and Tool has decided that the Drowned Cities, as an arena of perpetual war, represent his best natural venue.

Again, Bacigalupi shows us a meticulously rendered Darwinian existence that is not unleavened by caring and compassion, but against the larger debilitating forces of which small human lives avail not.

Tool of War opens up a short time later. Our Moreauvian hero has established himself as the general of a small army in the Drowned Cities and, using his superior knowledge and tactics, managed to emerge at the top of the local heap. But he does not reckon with a larger enemy. Mercier, the company that created him, has decided to find and eliminate their rogue “augment.” Under General Caroa, who had a hand in birthing and training Tool, the HQ where Tool is celebrating his victory is blown up. But our beastly hero escapes, although grievously wounded. He manages to reunite with Mahlia, who happens to be in the vicinity. She heals him, and then begins a cat-and-mouse game with Mercier and Caroa. The vast forces of the unethical and utilitarian corporation, pitted against a few pirates and one exceptional and exceptionally deadly creature. Finally, some familiar faces from Ship Breaker join the outlaws, and at the book’s climax, an incredible battle and face-to-face confrontation between the antagonists resolves into a bloody victory–but for whom?

This third installment in the sequence does some things differently than the previous two, whilst still proving to be an organic extension of the whole narrative arc. But certain things that were appealing in the first two books are sacrificed.

Ship Breaker was a quintessentially working-class or proletarian view of the future. We were intimately embedded in the day-to-day survival routines and rites and rituals of the untouchable caste of the future. (Lots of nice cultural details, such as new gods, featured.) Yes, Nita offered a glimpse into the empyrean realms of society, but she too was exiled into the muck. This focus on prole existence is all too rare in SF, and was much welcomed.

The Drowned Cities continued with its eye on the underclass, this time the cohort of war refugees embodied in Mahlia. We witnessed the plight of child soldiers as well. Again, the tale was far removed from the higher strata of society.

The third book abandons those realms for the more conventional and more omnipresent scenario of intercorporate intrigue and warfare, and we also venture into the “swank” world of Seascape Boston. Even our subsistence-level friends from the previous two books are now living rather large. And so the book instead hews to a certain cyberpunk standard. Yes, Tool’s quest for autonomy and survival is gripping. The reader feels his excruciations intimately. Bacigalupi tosses one peril and near-fatal escapade after another at the indomitable creature, who emerges as a combo of Tarzan, Wolverine (numerous similarities, from Tool’s creation backstory to his healing and destructive powers, obtain) and Roy Batty, the rebel replicant from Blade Runner. The symbolic level of child rebelling against father also hits home. But in the foregrounding of Tool’s superhuman quest, we inevitably and necessarily lose our view of what life on the ground is like for the Joe and Jane Filter-mask of this era. Bacigalupi’s sympathies with these people remain evident, but on the shelf, so to speak.

That said, the book delivers nonstop action, emotional bombs, and neck-twisting plot jolts, as well as examining moral issues of humanity versus their intelligent creations that Robert Repino is likewise considering in his War with No Name series. And there’s even mordant humor to hand. When one of the worst villains in the tale proves to be an innocuous looking young female named Arial Jones, whose military grade is Junior Analyst, you can practically hear Bacigalupi chuckling at the way life fails to live up to our desperate, errant clichés, in this era or others.