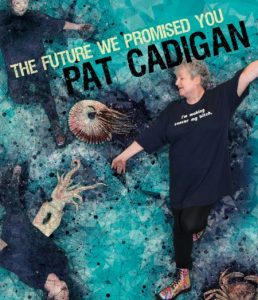

Pat Cadigan: The Future We Promised You

Patricia Oren Kearney was born September 10, 1953 in Schenectady NY and grew up in Fitchburg MA. She attended the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she studied theater, and the University of Kansas, where she studied SF writing under James Gunn, graduating in 1975. She met first husband Rufus Cadigan at UMass-Amherst; they transferred to the University of Kansas in Lawrence where she completed her undergraduate degree while he did his doctorate in theatre. While there, she joined the concom for MidAmeriCon, the 34th World Science Fiction Convention in Kansas City MO, held in 1976, where she was guest liaison for writer guest of honor Robert A. Heinlein. She worked at the Nickelodeon Graphics design firm for writer Tom Reamy until his death in 1977, then went to Hallmark cards as a writer and editor for a decade. She co-edited Chacal and Shayol with second husband Arnie Fenner; the latter ran from 1977-85, and they won a World Fantasy Award for their work in 1981. They have a son, Rob Fenner. In 1996, she moved to the UK, where she still lives with third husband Chris Fowler (not the author). In late 2014 she became a British citizen.

Her first SF story was ‘‘Death from Exposure’’ (1978). Notable stories include Theodore Sturgeon Memorial and Nebula Award finalist ‘‘Pretty Boy Crossover’’ (1986); Hugo, World Fantasy, and Nebula Award nominee ‘‘Angel’’ (1987); Hugo and Nebula Award nominee ‘‘Fool to Believe’’ (1990); Nebula Award finalist ‘‘The Power and the Passion’’ (1990); Hugo Award finalists ‘‘Dispatches from the Revolution’’ (1991) and ‘‘True Faces’’ (1992); British Fantasy Award finalist ‘‘Chalk’’ (2013); and BSFA finalist ‘‘The Emperor’s New Reality’’ (1997). ‘‘Lost Girls’’ (1993), ‘‘Paris in June’’ (1994), and ‘‘Datableed’’ (1998) were all longlisted for the James Tiptree, Jr. Memorial Award; “Paris in June” was also a Sturgeon Award finalist. “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out for Sushi” (2012) won a Hugo Award and the Seiun Award. Some of her short work has been collected in Bram Stoker Award-winner Patterns: Stories (1989), Home by the Sea (1992), and Dirty Work: Stories (1993). She also contributed six stories to Letters from Home (1991), which also included six stories each from Karen Joy Fowler and Pat Murphy. She edited The Ultimate Cyberpunk (2002).

Cadigan’s debut novel was Mindplayers (1987), a Philip K. Dick Award finalist. Second novel Synners (1991) was a Nebula Award finalist, won the Arthur C. Clarke Award, and established her as a major cyberpunk writer. Fools (1992) also won the Clarke Award. Her Doré Konstantin series includes Tea from an Empty Cup (1998) and Dervish is Digital (2000). She has also written film novelizations and tie-in work. Cadigan was a guest of honor at MidAmeriCon II, the 2016 Worldcon, where she hosted the Hugo Awards ceremony with help from writer Jan Siegel.

She was diagnosed with cancer in 2013, and had successful surgery. The cancer recurred in 2014, however, and she is still undergoing treatment. She writes about her experiences online at Ceci N’est Pas Une Blog: Dispatches from Cancerland, patcadigan.wordpress.com.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘I have only written things I was really interested in. When I was first writing cyberpunk, I wasn’t saying ‘I’m going to write cyberpunk now,’ I was just writing. So I keep on writing. Story first. Serve the story. It’s not so much that I’ve shifted. Society’s shifted. Is Cyberpunk dead? No. I told some people who were reading Synners for the first time, recently, ‘Well, there’s actually not as much science fiction in it as there used to be.’ People always say, ‘Where’s my flying car?’ That’s not the future we promised you. We promised you a dark technological dystopia. How do you like it?

‘‘We’ve given up a lot of privacy for the sake of convenience. I have seen the world’s population go from five-and-a-half billion to six billion to seven billion. I was alive when there were only three billion people. There are too many people to keep track of, personally, but people don’t have as much privacy as they used to. Take loyalty cards for example. They offer rewards and discounts for brand loyalty, but they also keep track of your purchases. I laugh at anyone who complains about privacy but has a Facebook account. Some people’s Facebook pages should be called ‘pleaseburgleme.com’ because they post photos of themselves on vacation while they’re away from home. And then there’s identity theft. If you steal my identity, though, all you’re going to get are my bill collectors. They’re going to come for you, pal. In any case, I don’t put anything online that I wouldn’t put on a sheet and hang on the front of my house. That’s just common sense. But for so many people, things seem less real when they’re just typing it on a screen.”

…

‘‘2013 was an up and down year. My mother died at the end of 2012. I was really busy, I got nominated for a Hugo Award, and then I got cancer. I can’t remember if the nomination came first – it was a roller coaster. Then the cancer was gone, it was cured, and I won a Hugo. I started working on a novel based on ‘The Girl-Thing who Went Out for Sushi’. The working title is See You When You Get There. I started it right after my mother died, because she wasn’t calling me on the phone anymore. I just put my head down, and when I looked up, two or three months later, I had 80,000 words. Not all of them were great, but a lot of them were worth keeping. I had a direction and the book was taking shape. Before that I’d taken on a lot of short fiction projects because I could complete them in a reasonable period of time between phone calls from my mother. I had taken on so many stories that I had to stop work on the novel for a year, because I had so many short fiction things to write. I didn’t mind. I came up in short fiction. I love short fiction, and I am who I am because I wrote short fiction for Ellen Datlow. She made me – she and Gardner Dozois. They’re very close friends of mine, but they’re consummate professionals. Ellen taught me how to cut ruthlessly and serve only the story, rather than indulge myself. Gardner taught me better sentence arrangement, how to make words more powerful. I write all the words, and I leave it there, and then I come back and cut needless words, and feel like a genius.”

…

‘‘One of the main characters in See You When You Get There, a woman named Zee, had a pen pal on Earth back when she was a kid. Because of the time difference, they couldn’t just talk back and forth – there are no ansibles. She did a virtual visit where she piggybacked on someone on Earth so she could go through a day with him. It felt so rushed to her – you’re up in the morning, and before you’re even awake you’re expected to go to school, and just as things are getting started with school you have to stop and eat lunch, wolf down your food and go back to classes, and then just when you should be entering the most productive part of the day, you have to rush home, rush through your leisure time, and then you have to go to bed. You’re barely in bed when you have to get up and do the whole thing again. The weeks go fast too: ‘Every time you turn around, it’s Tuesday.’ She feels like time is rushing past, but she can’t get anything done. There’s no escape from Tuesday. It keeps coming until it Tuesdays you to death. The kids on Earth have to do their visits to the outer planets in installments, because everything takes such a long time there, and they can’t do it all at once. They have to do it in half-day installments, and not as much happens.”

…

‘‘If you brought in someone from 1700 right now, they’d probably end up over in the corner, curled up in the fetal position, because of the noise and the crowding. Something happened with my husband, before we were married. When he came from London and stayed with us in Kansas for six months, one day he took to his bed. I said, ‘Are you okay?’ He said, ‘The sky is so big and it’s always pressing down on me.’ I read up on that. When settlers moved West, they’d have this thing where they felt they were going to fall into the sky. That was it: from horizon to horizon, there was just sky. My husband and I are both urban creatures. We live in Zone 3 in London, not in the center but not the suburbs. When we got together I said, ‘Just don’t tell me that you want to move out of London into the middle of nowhere.’ He said, ‘Oh, no.’”

…

‘‘I’ve been keeping a cancer blog, which anyone can access. I started it as a way of working things out, and not just for myself. My having cancer has been awkward for some of my friends. One of the things I posted on my blog was: ‘You don’t have to say anything to me. I know you don’t know what to say. I didn’t know what to say when my friends with cancer told me about it. If we were friends before I was diagnosed, we’re still friends now, and you’re off the hook for finding perfect things to say, because only my oncologist has the perfect thing to say.’ Everyone handles the disease differently. I remember something another cancer patient said, about ‘‘fighting cancer,’’ how he didn’t like describing it that way because it made him feel he was at war with his own body. I don’t feel the same way, but I understand the perspective. I’ve since discovered that I have a number of fellow travelers who aren’t saying anything about their conditions for good reasons of their own. They don’t need to explain themselves – everyone has to handle it in the way that’s best for them.”

Read the complete interview in the November 2016 issue of Locus Magazine. Interview design by Francesca Myman.