Paolo Bacigalupi: The Windup Boy

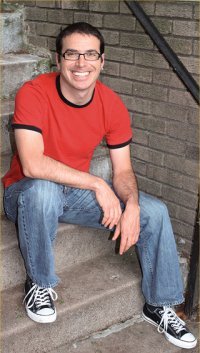

Paolo Bacigalupi was born in Colorado Springs, moving with his hippie parents to western Colorado soon after. They lived in a commune briefly and remained in the area afterward; when his parents divorced he split his time between them, going to various schools, finishing high school at the private Colorado Rocky Mountain School, where he learned the basics of writing. He attended Oberlin College in OH, where he met his wife-to-be Anjula (they married in 1998) and majored in East Asian Studies, spending time in China for foreign-language immersion.

Paolo Bacigalupi was born in Colorado Springs, moving with his hippie parents to western Colorado soon after. They lived in a commune briefly and remained in the area afterward; when his parents divorced he split his time between them, going to various schools, finishing high school at the private Colorado Rocky Mountain School, where he learned the basics of writing. He attended Oberlin College in OH, where he met his wife-to-be Anjula (they married in 1998) and majored in East Asian Studies, spending time in China for foreign-language immersion.

Bacigalupi is a frequent contributor to F&SF, publishing his first story there, ‘‘Pocketful of Dharma’’, in 1999, though he first came to wide attention with Sturgeon finalist ‘‘The Fluted Girl’’ (2003) and Hugo and Nebula Award nominee ‘‘The People of Sand and Slag’’ (2004). His work has also appeared in Asimov’s, various anthologies, and High Country News. Other stories include ‘‘The Pasho’’ (2004), Hugo nominee and Sturgeon Award winner ‘‘The Calorie Man’’ (2005), ‘‘The Tamarisk Hunter’’ (2006), ‘‘Pop Squad’’ (2006), Hugo and Sturgeon Award finalist and Asimov’s Award winner ‘‘Yellow Card Man’’ (2006), ‘‘Small Offerings’’ (2007), ‘‘Softer’’ (2007), and Hugo, Sturgeon, and Nebula Award nominee ‘‘The Gambler’’ (2008). Many of his stories were collected in Locus Award winner Pump Six and Other Stories (2008).

His first novel The Windup Girl (2009) was a huge critical and commercial success, named one of the top ten fiction books of the year by Time magazine, and won Hugo, Campbell Memorial, Compton Crook, Locus, and Nebula Awards. His first YA novel Ship Breaker (2010) won the Michael L. Printz Award, was nominated for the Andre Norton Award, was a finalist for the 2010 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, and made the Top Ten Best Fiction for Young Adults list, presented by the American Library Association’s Young Adult Library Services Association.

‘‘There are a lot of things in my writing that somebody can find to hate. If you’re looking for escapism, you’re not necessarily going to find it. If you’re looking for something really nifty and cool, you’re not necessarily going to find it. If you’re looking for an exploration of fears, you’re gonna find it! That’s where I work. Is the world going to fall apart? And if so, what is it going to look like? I’m interested in the process of us not getting our shit together.”

…

‘‘The success of The Windup Girl makes me wonder whether or not we even know what the term ‘science fiction’ means to people. I hope my novel uses the same tools science fiction has always used, but turns them to some pressing, timely concerns of today. Maybe science fiction lost its track a little bit, and got off on some lines of speculation which are pretty interesting but not necessarily connected to today’s questions, as previously it had been core to our conception of ourselves and where we were headed. You want our genre to be perceived as the most relevant of storytelling methods. That science fiction is specifically about our world and what’s going on with it, imposing a sense of meaning over that world that otherwise is muddy.

‘‘The success of The Windup Girl makes me wonder whether or not we even know what the term ‘science fiction’ means to people. I hope my novel uses the same tools science fiction has always used, but turns them to some pressing, timely concerns of today. Maybe science fiction lost its track a little bit, and got off on some lines of speculation which are pretty interesting but not necessarily connected to today’s questions, as previously it had been core to our conception of ourselves and where we were headed. You want our genre to be perceived as the most relevant of storytelling methods. That science fiction is specifically about our world and what’s going on with it, imposing a sense of meaning over that world that otherwise is muddy.

‘‘I’d sold my YA Ship Breaker before I sold The Windup Girl – it’s just that the publishing schedules were different. There were a lot of reasons why I wrote a novel for young adults, and Ship Breaker was sort of an attempt to meld all of those goals into a single project. One of the reasons, baldly, was needing to find a way to support myself as a writer. I kept hearing how nobody was buying science fiction for adults anymore and that it was impossible to support yourself there, but then I read this profile of Scott Westerfield where he said, essentially, ‘All my friends who write YA are supporting themselves as writers.’ That was an ‘aha!’ moment for me. If you keep ramming your head against the wall, expecting a different outcome, maybe you ought to try finding a door. And YA was one of the doors that I decided to push on.

‘‘It actually fit quite well for me, because it connected to some other problems with my writing, and its effectiveness, that I’d been thinking about. And a lot of that boiled down to audience. Who did I need to talk to, in order to have an impact on the world? One of those groups, in my mind, is young people. As adults, we’re stuck in this matrix of decisions that we’ve already made. If you’ve got a mortgage to pay and you’ve got your commute already set up, you keep getting in your car and driving even as you kill the planet. We’re unwilling to make the more difficult decisions that would pull ourselves out of that matrix. But when you speak to young people, you’re speaking to people who haven’t cast all their choices in stone yet. They still have options; it’s all in flux. So to have an opportunity to talk to them about the world that we’re handing off to them is really valuable, and really wonderful to me.”

‘‘It actually fit quite well for me, because it connected to some other problems with my writing, and its effectiveness, that I’d been thinking about. And a lot of that boiled down to audience. Who did I need to talk to, in order to have an impact on the world? One of those groups, in my mind, is young people. As adults, we’re stuck in this matrix of decisions that we’ve already made. If you’ve got a mortgage to pay and you’ve got your commute already set up, you keep getting in your car and driving even as you kill the planet. We’re unwilling to make the more difficult decisions that would pull ourselves out of that matrix. But when you speak to young people, you’re speaking to people who haven’t cast all their choices in stone yet. They still have options; it’s all in flux. So to have an opportunity to talk to them about the world that we’re handing off to them is really valuable, and really wonderful to me.”

…

“I’m just wrapping up this YA novel The Drowned Cities, my follow-up to Ship Breaker (it’s not a sequel). I rushed the first draft in order to meet my deadline, but I hadn’t succeeded in putting the right words on the page. So I threw everything away except for one paragraph of exposition that had seemed powerful to me, and basically I used that as the prompt. It took me two years to write, but it’s the right book, now. If nobody had been willing to buy it, I would self-publish it, because it does what I wanted it to do. That’s the kind of thing I’m hunting for now with my writing, more than anything else. Stories that mean a lot to me, and that I hope will mean a lot to readers.”

Excerpts from the interview:

Excerpts from the interview:

Pingback:Paolo Bacigalupi: The Windup Boy - Locus Online | Science Fiction Research | Resources | Scoop.it

Pingback:Paolo Bacigalupi: The Windup Boy - Locus Online | Young Adult Books | Scoop.it

Pingback:Quote of the Day | Fantasy Belongings

Pingback:The Great Geek Manual » Geek Media Round-Up: August 22, 2011

Pingback:Geek Media Round-Up: August 23, 2011 – Grasping for the Wind

Pingback:Paolo Bacigalupi: The Windup Boy - Locus Online | The Joy of Children's Literature | Scoop.it

Pingback:Fantasy Blogosphere: August 29, 2011 | Fantasy Book News