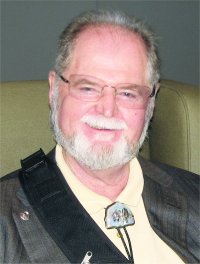

Larry Niven: Tell Me a Story

Lawrence Van Cott Niven was born in Los Angeles and attended the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena from 1956-58, but didn’t graduate. He got his BA in mathematics from Washburn University in Topeka KS in 1962, then returned to California to do post-graduate work at UCLA from 1962-63.

Niven began freelance writing in 1964, the year of his first short fiction publication, “The Coldest Place”, in If. He won his first Hugo in 1967 for “Neutron Star”. His other Hugo winners are “Inconstant Moon” (1971), “The Hole Man” (1975), and “The Borderland of Sol” (1975).

First novel World of Ptavvs (1966) began his vast Known Space future history. Ringworld (1970) won both the Hugo and Nebula and began a series that includes The Ringworld Engineers (1979), The Ringworld Throne (1996), and Ringworld’s Children (2004). His other solo novels are A Gift from Earth (1968), Protector (1973), A World Out of Time (1976), The Magic Goes Away (1978), The Patchwork Girl (1980), The Smoke Ring (1987), The Integral Trees (1994), Destiny’s Road (1997), and Rainbow Mars (1999).

Niven is known for his collaborations, especially with Jerry Pournelle, beginning with The Mote in God’s Eye (1974) and continuing with Inferno (1975), Lucifer’s Hammer (1977), Oath of Fealty (1981), Footfall (1985), The Gripping Hand (1993), The Burning City (2000), Burning Tower (2005), and Escape from Hell (2009). With Steven Barnes he wrote a series of virtual reality novels: Dream Park (1981), The Barsoom Project (1989), and The California Voodoo Game (1992), plus standalones The Descent of Anansi (1982), Achilles’ Choice (1991), and Saturn’s Race (2000). With both Barnes and Pournelle he wrote The Legacy of Heorot (1987), The Dragons of Heorot (1995; as Beowulf’s Children in the US). With Pournelle and Michael F. Flynn he wrote Prometheus Award winner Fallen Angels (1991). He expanded the Known Universe world with novels co-written with Edward M. Lerner: Fleet of Worlds (2007), Juggler of Worlds (2008), and Destroyer of Worlds (2009). With David Gerrold he wrote The Flying Sorcerers (1971), and with Brenda Cooper Building Harlequin’s Moon (2005). Berserker Base (1984) was written with Poul Anderson, Edward Bryant, Stephen R. Donaldson, Fred Saberhagen, Connie Willis, and Roger Zelazny.

Some of his stories and essays are collected in Neutron Star (1968), The Shape of Space (1969), All the Myriads Ways (1971), The Flight of the Horse (1973), Inconstant Moon (1973), A Hole in Space (1974), Tales of Known Space (1975), The Long Arm of Gil Hamilton (1976), Convergent Series (1979), The Time of the Warlock (1984), Niven’s Laws (1984), Limits (1985), N-Space (1990), Playgrounds of the Mind (1991), Bridging the Galaxies (1993), Crashlander (1994), Flatlander (1995), Scatterbrain (2003), and The Draco Tavern (2006). Retrospective The Best of Larry Niven is forthcoming.

He edited The Magic May Return (1981) and More Magic (1984), with stories set in the world of The Magic Goes Away, and edited several volumes of the Man-Kzin Wars anthologies. He has also written for comic books and television.

Niven won a Heinlein Award (2005) and a Hubbard Award for Lifetime Achievement (2006). He lives in Southern California with wife Marilyn Wisowaty (married 1969).

Excerpts from the interview:

“I try to be versatile. I’m in awe of other people’s versatility. Silverberg, for instance, has done everything. I’ve reached as far as I could in every direction I could see. (Isaac Asimov once called me his ‘spiritual son,’ and I refrained from telling him I’m everybody‘s spiritual son.) Also, there are benchmarks that probably wouldn’t be visible to a younger writer but were topics that everybody touched on when I was a kid. I’ve done my solipsism story. I’ve done time travel: the traveler from the Institute for Temporal Research who keeps finding fantasy creatures. First man on the moon. There are a few I haven’t tried — it’s hard to believe in an invisible man, for instance. But interstellar war? Sure.

“In Poul Anderson’s universe, most stories cover only a small part of the galaxy. Flandry’s domain isn’t the entire galaxy; there are a lot of worlds, but it’s a tight little corner and Anderson’s not trying to be E.E. Smith. I decided he was right, and I made Known Space 30 light years across. There’s plenty of room for expansion, and that’s the way I played it. Known Space is all of the space that the aliens you know have explored. Human Space is the space you think you control. Of course, you have to dance lightly over that term, because what you think you control is interspersed with what the Outsiders think they control, for instance, and that’s everything from Jupiter on out.

“Hard SF is not basically funny until you look deep into it — or maybe I should say, you have to be either very shallow or very deep to find the funny spots in hard science fiction. Once you understand enough about Known Space, you reach the point at which Earth is so crowded that picking pockets has become a sport, and your wallet always has a stamp on it.”

*

“John Campbell turned down every one of my stories, except maybe the last one. (Given the timing, it’s hard to know — he may have accepted ‘Cloak of Anarchy’.) But I got a letter from him for the first version of a story called ‘Arm’, 12 pages of detailed work on what’s wrong with it and how to rethink it. And I used it very extensively and rewrote it. Campbell was everybody’s editor! But Analog never published me until after his death.

“As for Horace Gold, he was gone when I started writing. My first sales were to Frederik Pohl, who was editing Galaxy and Worlds of If and Worlds of Tomorrow at the time. Fred Pohl discovered me. Of course, I was ready to be discovered. I got in just as the New Wave was gearing up, and the New Wave concentrated on characterization and avoided standard storytelling framework, with lots of room for innovative typing.”

*

“Jerry Pournelle and I have been persuaded that we ought to menace the Earth with something big again. This time, we’re going to try to stop it. It’s likely to be a very political novel, so I’m flinching a little, but Jerry’s going to have to cover that.

“I’ve been involved in politics before. Sigma is an organization of science fiction writers who are willing to do things for the government, run by a guy named Arlan Andrews. I got involved with that, partly because Jerry wants me to know about bureaucracies for the next novel. I am not the most important person involved. I’ve had little to contribute. I thought I might do some good, but my mind doesn’t seem to be the right structure. I’m not coming up with ideas for how to attack the United States — or others come up with those (how to do that and how to stop it) a lot faster. I’ve got friends who have been in the military and others who haven’t, and all are better at this than I am at finding near-term threats.”

*

“I don’t often think about what my career has meant, but every so often I get reminded. E-mail comes in from total strangers who say I’ve shaped their lives. And of course I made my landmark when the Soviet Union came down. The Soviet Union was driven bankrupt by a plan evolved at my house in Tarzana, with Jerry Pournelle in charge. We called ourselves the Citizens’ Advisory Council for a National Space Policy. When it seemed apparent that Ronald Reagan was going to be president, it also seemed apparent that his science advisor was going to be Jerry Pournelle’s top student. On that basis, we’d have access to the president. Jerry borrowed our house and threw a weekend that eventually became six weekends over about 10 years, during the first few of which we evolved what came to be called Star Wars, although the preferred title was the Strategic Defense Initiative. For a while, I believed they hadn’t built anything to back up the SDI; they just talked about it and evolved it as a plan of action. On that basis, the Soviet Union was taken down by a science fiction story written at Larry Niven’s house! Which was wonderful.”

Read the full interview in the September 2009 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.