Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Ivory Apples by Lisa Goldstein

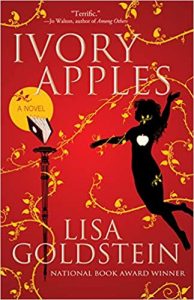

Ivory Apples, Lisa Goldstein (Tachyon 978-1-61696-298-2, $15.95, 276pp, tp) September 2019.

Ivory Apples, Lisa Goldstein (Tachyon 978-1-61696-298-2, $15.95, 276pp, tp) September 2019.

In a career now well into its fourth decade, Lisa Goldstein has made something of a habit of confounding expectations: she made a stunning debut with her Holocaust fantasy The Red Magician, veered off into student revolutions and Surrealism in The Dream Years, dabbled with dystopia in A Mask for the General and her own brand of magical realism in Tourists, explored historical fantasy in Strange Devices of the Sun and Moon and The Alchemist’s Door, and most recently turned to time-travel with Weighing Shadows, a “change war” story that bears comparison with the Annalee Newitz novel reviewed above. By itself, this broadly ecumenical approach to the fantastic, together with her consistently graceful prose and compelling characters, ought to have made her more of a household name by now – but unpredictability isn’t always a marketable virtue, and Goldstein’s further habit of subtly undermining the conventions that she employs probably doesn’t help, even as it makes for richer and more complex fictions. With Ivory Apples, she takes on the nature of fantasy and storytelling itself, in a tale with enough coming-of-age elements and family crises to qualify as a good YA novel, a magical grove where muses hang out, a reclusive author of a classic fantasy work, and an obsessive fan villainous enough to make Stephen King’s Annie Wilkes look merely peevish.

The teenage narrator, Ivy, is the oldest of four sisters whose mother has died and whose father Philip, a professor at the University of Oregon, spends much of his time managing the affairs of their great-aunt Maeve. Decades earlier, Maeve pseudonymously wrote a beloved fantasy novel called Ivory Apples, but she has since retired into Salinger-like reclusiveness in her remote country home. Only Philip and the girls know her true identity or visit her regularly, and the girls have grown up protecting the great family secret. But on one such visit, Ivy crosses a stream in the woods near Maeve’s house – a classic fantasy-portal move – and finds herself in a grove full of what appear to be pointy-eared fairies, with Aunt Maeve herself floating comfortably nude in the lake. Maeve warns her to go home at once, but before she does, she feels a presence pushing its way into her body. The presence turns out to be an anarchic sprite which Ivy dubs Piper, after a chapter in The Wind in the Willows. It’s not the only allusion to classic fantasy in the novel, and what little we learn of Ivory Apples itself carries echoes all the way back to Lud-in-the-Mist and earlier.

This odd family arrangement is quickly upended when the children are befriended by a charming but rather too-friendly lady named Kate Burden, whom Ivy instantly distrusts and rightly suspects is up to something. It’s not long before a family tragedy places the children in her care, and not long after that that Ivy finds herself homeless, surviving on the streets with the aid of the resourceful but unreliable Piper. Goldstein’s pacing becomes one of the novel’s most haunting aspects, as months and even years pass between critical junctures in a narrative that feels headlong, but we’re pretty sure that this is all going to lead toward some confrontation involving Maeve, the real story behind Ivory Apples, and those deceptively innocent woodland sprites. It’s a bit risky for any writer to appear to reinforce the old myth that artistic creativity arises from some sort of muse-like supernatural intervention, but Goldstein skillfully balances this conceit with serious questions about the origins and uses of the imagination; each of her characters, from Ivy, to her sisters, her great-aunt, her father, and the ominous Kate Burden, can be viewed through the lens of how they deploy, or fail to deploy, imagination. On the one hand, Ivory Apples is a haunting story of what a classic fantasy work can do for and to its readers and its creator; on the other, it’s a pretty wonderful, clear-eyed, and unsentimental fantasy novel entirely on its own terms, muse or no muse.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the September 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.