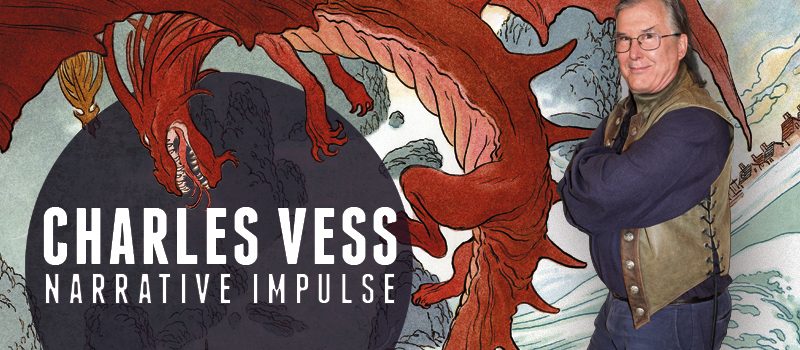

Charles Vess: Narrative Impulse

Charles Vess was born June 10, 1951 in Lynchburg VA. He attended Virginia Commonwealth University, graduating in 1974 with a BFA, and worked in commercial animation until moving to New York City in 1976. There he became a freelance illustrator, working for many publications including Heavy Metal, Klutz Press and National Lampoon. For over 10 years he worked for various comic book publishers, including Marvel, DC, and Dark Horse. He wrote, drew, and painted the Spider-man graphic novel Spirits of the Earth (1990), and illustrated Neil Gaiman’s World Fantasy Award-winning Sandman comic “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1990).

His many awards include the Ink Pot Award for Excellence in Comic Art (1990), three World Fantasy Awards for best artist, an Eisner Award for best penciler/inker and one for best painter. He has won two Chesley Awards and two Locus Awards for his art as well.

His latest major project is The Books of Earthsea (2018) an illustrated compendium of Le Guin’s classic series, produced in close collaboration with the author. This 1000+ page work features 56 color and b&w illustrations. Vess and his wife Karen live in the Appalachian foothills.

Excerpts from the interview:

“I started drawing when I was old enough to grab a crayon and crawl over to the wall. Don’t try this at home, right? I always drew. I drew comic books, and at some point in middle school, I discovered how to draw a tank. That was good for that time period – you needed to explode some things. Making art and going to art school were the only things I ever wanted to do. In high school, when I asked the people I hung out with for four years in the art club and classes, which art school they were going to, they all looked at me like, ‘Are you crazy? We’re going somewhere where we can make money.’ I went to VCU, Virginia Commonwealth University, in Richmond VA. I wanted to learn how to do illustration, but they didn’t have an illustration department, and their commercial art department wasn’t for me. I switched into fine arts and they taught me a lot of things, but nothing about how to draw a figure. If you put a figure in a drawing, it became narrative. If it was narrative, it wasn’t art. One of my professors painted corners of rooms for ten years. Empty corners of rooms.

“I worked for a few years at an animation studio in Richmond, and then Michael Kaluta, who had gone to the same school and was a friend, offered me half of an apartment in New York, so I moved there. It was rent controlled, so I paid $125 a month for a little tiny apartment. The bed rolled up into the closet. I took my portfolio around to publishers. Back then, you dropped off your portfolio in the morning and picked it up in the afternoon, and you tried to figure out some way to tell if they’d actually looked at it, like putting a little piece of hair across it, or hidden tape – everything you could think of, because how could you know? Most of the jobs I got were through word-of-mouth, through people I knew. I was 26 when I moved to New York, so I wasn’t quite a beginning artist, but I was still stumbling around. The only time I had a nine-to-five job, I had a friend – Shary Flenniken, who used to draw Trots and Bonnie for the National Lampoon, and she asked me if I would be her assistant. I worked there at the National Lampoon for about six months. Then I started getting more work, and I needed to be at home doing it.

“You may remember there was an hour long Rankin/Bass-produced TV show of The Hobbit, and Abrams Books, the big art publishing company, was going to do the entire text of The Hobbit using illustrations from the show. Since the show had edited the story a lot to fit it into an hour, they hired artists to fill in the rest. I was the barrel artist. When all the hobbits get in barrels to go down the river to Laketown – I drew all those. The quicker you could paint them, the quicker they’d give you more to do. It was fun to have a book in every bookstore at Christmastime with my name in minuscule type at the front. Otherwise, it was a grab-bag of different kinds of work. I did some art for Singer Sewing Machines, in-house brochures – Santa and the happy elves with their sewing machines – all those things that sort of send a shiver up my spine now when I think about them, but it paid the rent.

“I’m certainly better now at thinking through a concept and I’m better at drawing a figure than I was when I was younger. It was tough to get the practice, and tough to get published. Early on, I discovered that I really had no pulp sensibility, so if I tried to draw Tarzan or Conan the Barbarian, they looked kind of goofy. It took years to realize that’s not what I should be doing. Everyone said I should be drawing children’s picture books, but I would go to children’s book editors and they would say, ‘Oh, you should be drawing comic books.’ Back and forth, back and forth.

“The first time I felt like I’d found my place, someone called me instead of me calling them. That was good. It was Byron Preiss, who used to package books, and he had had an entire graphic novel drawn by Alex Niño adapting More Than Human by Theodore Sturgeon. My job was to go in and fix things, and put more color in, and so on. It took a long time. Robert Wiener, who is well known now as the publisher of Donald Grant Books, had a small press back then, and he published my first book. He gave me $750 to write and draw whatever I wanted. It’s called The Horns of Elfland – I think it’s 64 pages. I wrote and drew three different stories in it, and ultimately a couple other things for him. It took a long time for me to find what I was actually good at.

“I’ve always written. I still have my little treasure trove of school papers with stories that were as much Ray Bradbury as I could be, or as much Lord Dunsany as I could be, and no one will ever see those, but I’m very happy I still have them. I like to tell stories. They can be written, or they can be drawn. One of my favorite things to do is to paint an image that has a narrative impulse and a title that’s very evocative, and hopefully the viewer will tell themselves their own story. Hundreds of people will see that painting, and each one will have their own story, I hope.

“I started getting offered jobs in comics. I learned what was called the Marvel Method way back when, which was that the editor, yourself, and the writer would go out to lunch, and you’d hammer out a story idea; the writer would type it up at about a page and a third; and then they gave that to the artist, and you made it into a 22-page comic. You had to invent lots of things, and dialogue was one of them, because if you didn’t know what they were saying, then you had these frozen faces, and your art was really boring to look at. I would just start writing in dialogue, which drove the writers crazy because they’d have to erase it all and put in whatever they wanted instead, but it helped me. I had a particular type of story that I enjoyed, which wasn’t pulp – it was more Lord Dunsany, more Ray Bradbury, more poetic, and finding publishers that were interested in that was not easy. It took a long time for me to realize that the better writing you work with, the more it pulls out of the art, and the better your art will be. When I started working with Neil Gaiman, that was really fun, and very collaborative.

“That was a big leap. Before I met Neil, I’d come up with a story for Spider-Man, and I sent him to Scotland because I wanted him out of New York City. I wanted to be able to go there and enjoy myself and draw all of Scotland. I wrote and drew and painted the book, and it was delayed and delayed and delayed. Then at San Diego one year, Neil was wandering down the hall – this was when he could wander down the hall without being mobbed – and we started talking. He had written a letter to one of these comic fanzines in defense of a drawing that I’d done that was referencing James Branch Cabell, the writer and fantasist. We started talking about him, and got off onto discussing many other writers that we both enjoyed. He suggested I draw an issue of Sandman, and he went back home, and I went back home. He saw an edition of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that I’d illustrated, just the text of the play and my pictures, and he called me up and said, ‘I’ve got this idea, but we’ve got to really change what all the characters look like.’ It was a fun thing to draw, because we were really collaborating. He would write stories and ideas that he wanted to see me draw. That was ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, Sandman #19, the issue that won the World Fantasy Award. That and the Spider-Man graphic novel, Spirits of the Earth, came out within months of each other, which cemented my retail recognition, and everything became easier from that point on.”

Interview design by Francesca Myman. Photo by Liza Groen Trombi.

Read the complete interview in the January 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.