Lila Garrott Reviews Foundryside by Robert Jackson Bennett

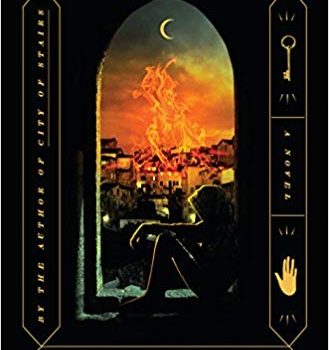

Foundryside, Robert Jackson Bennett. (Crown 978-1-5247-6036-6, $27.00, 512pp, hc) August 2018.

Foundryside, Robert Jackson Bennett. (Crown 978-1-5247-6036-6, $27.00, 512pp, hc) August 2018.

Foundryside is the beginning of a new fantasy series, and is Robert Jackson Bennett’s first novel following the extremely well-received Divine Cities trilogy. It mostly lives up to expectations, managing to combine a large-scale story with an interesting world, relatable characters, and a complicated magic system; it also demonstrates, as the Divine Cities trilogy did, that Bennett’s interests lie firmly in questions about the morality of power. His worlds are places where powers on a divine scale have definitely existed, and have shaped human society in usually damaging ways. The analogy to the current state of our own nuclear-age world exists, but is never belabored.

In Foundryside, the city of Tevanne is the head of an upstart empire, running on magical technology passed down incompletely from the semi-mythical Hierophants. The four merchant houses of Tevanne make self-propelling carriages, floating and inextinguishable lanterns, and other such useful objects by inscribing sigils that make the objects believe the state of reality is different than it actually is. From this, the four houses have gained massive wealth and power, subjugating huge portions of the world outside Tevanne and instituting a plantation-slavery-based colonial system. Inside the city, the houses live in luxury within the secure walls of their campos, allowing no greater authority than their own. Since no government is permitted in the cracks between the campos, the remaining city is a lawless place of makeshift rookeries, vice, poverty, and violence.

Sancia, the protagonist, survives by thievery, exploiting an unfortunate past incident which gave her strange powers. As is often the way with thieves good enough to command a high price, she is hired to steal something which turns out to be dangerous, both politically and otherwise: a talking key that can open any lock. Together, Sancia and her new key/friend Clef must evade the officers of whatever merchant house is looking for them, as Sancia does not trust that any of the houses would use the power Clef represents well, and also find some way to leave the city. The various parties interested in Clef would prefer this not happen, as would Gregor Dandolo, the young merchant house heir and war hero who is tortuously trying to set up an actual civil authority in the waterfront district. Catching a thief of Sancia’s stature would be the boost he needs to make the houses start taking him seriously.

The inter-house feuding and the general mayhem that follows in Sancia’s wake are complicated and believable, but never overly confusing. There is something of a Venetian flair to the culture and habits of the houses, which have the names of great Venetian families: Dandolo, Candiano, Michiel. This encourages the idea that the Hierophants were in some way equivalent to the Roman Empire, and in fact there are a lot of Latin names and fragments in Hierophant material. The correspondence set up between Venice, also an empire built on the shards of another, and Tevanne is helpful in understanding both the political and cultural situations, but is subtle enough that one doesn’t need to put these pieces together to comprehend the plot.

Sancia is an enjoyable protagonist, and while most of the other characters fit somewhat into types – the cranky but lovable mad scientist and his amazingly competent assistant, the renegade anarchist collective of magical technicians, the sexist and scheming house head who isn’t as smart as he thinks he is – they’re well-drawn types, and they set off interesting reactions in one another. Sancia herself is three-dimensional, marked by a massive case of PTSD and an inability to jettison her sense of empathy, as much as she might like to.

The novel’s major flaw is that the magic system is so complicated, and so interwoven with the politics, that the first quarter or so of the book has been overtaken by infodumps to the point of as-you-know-Bob-ism. There’s a massive amount of information that the reader has to have before things can really get going, and it isn’t threaded into the beginning of Sancia’s heist as carefully as it might be. Fortunately, this problem does not persist into the later portions of the book.

Overall, this is both a reasonable stand-alone and a work which can clearly support sequels; it’s a thoughtful examination of the ways in which power can and might corrupt, with some spectacular action sequences in which a lot of things blow up, and a really thorough exploration of the nooks and crannies of its magic system. It will be interesting to see where Robert Jackson Bennett takes it from here.

This review and more like it in the August 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.