2017: The Year in SF by Russell Letson

[Editor’s note: part of our 2017 year-in-review essay series from the February 2018 issue of Locus]

[Editor’s note: part of our 2017 year-in-review essay series from the February 2018 issue of Locus]

But Serially –

Perhaps more emphatically than usual, this annual reflection should be labeled My rather than The Year in SF, since the sample is not only smaller than usual but skewed: only four of the 2017 novels I reviewed are free-standing (and two of those might not count as fully such – see below), with the rest belonging to some variation on the series.

Not that there should be anything wrong with that – as Peter Nichols and David Langford point out in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, the practice of extending a narrative or elaborating and re-using an invented world or cast of characters has been a feature (not a bug) of the field since before there was even a separate SF/F genre space. Nevertheless, they observe that “series” has come to indicate “multi-volume packaged commercial product.” (Some commentators might scornfully insert “extruded” in there as well.) So should I feel guilty about these particular pleasures? The snobby little neophilic devil on my left shoulder whispers that a series is the extruded essence of The Same Only Different and bait in the trap of mere comfort-reading. To which the little hedonistic devil on my right paraphrases Frank Zappa: We’re all reading genre-theme-and-variations here, and don’t kid yourself.

But when are multi-volume book products actually single narratives presented (usually) as trilogies – descendants of the Victorian three-decker by way of Tolkien? Ian MacDonald’s Luna: Wolf Moon is the middle volume of a big three-part novel that earns every page of its sprawl in an examination of the politics, economics, and socio-familial-sexual dynamics of its world(s). Almost as a byproduct, it also constructs a compelling hard-SF futurescape in which to run a twisty blood-feud revenge-tragedy plot machine. Ken MacLeod’s The Corporation Wars: Emergence is the last section of another single story spread across three volumes bursting with motifs, tropes, and Big Ideas about politics, economics, space-war, interstellar exploration and colonization, artificial intelligence, and virtual reality. Also, more politics. Neither of these busy and bustling constructions is what you’d call comfy or comforting, though they are plenty stimulating.

Sprawl has never been a flaw in SF – the point is usually, after all, that it’s a big universe out there, and big stories are needed. What’s interesting is the way an imagined world can contain not only Big Ideas or Big Actions but multiple kinds of stories, multiple genres. James S.A. Corey’s Expanse series has managed to do this right from the start, layering hard-boiled noir onto hard-SF motifs onto invasive-alien-technology onto space operatics – and that’s just in the first three books. The seventh, Persepolis Rising, adds a conquering totalitarian regime and an underground (well, behind-the-bulkheads) resistance movement to the mix, and then ends with hints about possible plot/genre complications to come. Neal Asher has played a similar game with his Polity universe by spinning off sub-series and then bringing elements from them back to recombine into even more outrageous adventures, which means that even though Infinity Engine completes the Transformation three-decker sub-series, we should not be surprised to see fallout from it turn up in a later sequence. In both cases, it is the scale and variousness of the worlds as much as the story lines or casts of characters that attract.

Sprawl has never been a flaw in SF – the point is usually, after all, that it’s a big universe out there, and big stories are needed. What’s interesting is the way an imagined world can contain not only Big Ideas or Big Actions but multiple kinds of stories, multiple genres. James S.A. Corey’s Expanse series has managed to do this right from the start, layering hard-boiled noir onto hard-SF motifs onto invasive-alien-technology onto space operatics – and that’s just in the first three books. The seventh, Persepolis Rising, adds a conquering totalitarian regime and an underground (well, behind-the-bulkheads) resistance movement to the mix, and then ends with hints about possible plot/genre complications to come. Neal Asher has played a similar game with his Polity universe by spinning off sub-series and then bringing elements from them back to recombine into even more outrageous adventures, which means that even though Infinity Engine completes the Transformation three-decker sub-series, we should not be surprised to see fallout from it turn up in a later sequence. In both cases, it is the scale and variousness of the worlds as much as the story lines or casts of characters that attract.

Scale of setting isn’t everything, though. Most of the 18-and-counting novels of C.J. Cherryh’s Foreigner sequence take place not only on one planet but in the confines of an aristocratic court, or country manor, or the corridors of bureaucracy – and even when off-planet, in the tight quarters of a starship or orbital habitat. The expanses traversed are cultural and psychological: across the emotional gaps between intelligent species that can get along only by remaining aware of those mental distances. Convergence continues two important developments in the series: the inclusion of the viewpoint of an alien character (and an alien child at that), and the title-signaled shift to more emphasis on political-cultural-familial processes and less on shooting and ducking and derring-do, (though shots are fired and some derring does get done). Nancy Kress also likes to put humankind face to face with Others, and in Tomorrow’s Kin they are us, sort of – distant cousins whose intentions are not immediately clear and whose attentions are not entirely welcome. It’s the opening of a trilogy that promises to keep turning its riddles over to reveal new sets of riddles.

Cherryh’s Foreigner novels have been appearing regularly for more than 20 years, but she is not the only marathoner. Charles Stross has been keeping two series going for more than a decade: the eight volumes of the Laundry (from 2002), and another eight (before revision and consolidation) of the Merchant Princes (from 2004). Both series had new entries in 2017, and both reflect the growing darkness that has worked its way into these already-dark worlds. Empire Games is the first-of-three in a new, next-generation movement in the Merchant Princes sequence, with the emphasis shifted from economics and politico-cultural change to matters of espionage and heartless, Cold-War-style covert operations in which very bad things are done by people who might only be scared stiff and desperate. Over in the more overtly terrifying world of the Laundry, The Delirium Brief continues to mine the metaphysical and political direness that lurks beneath the jokes about government bureaucracies. Both series continue to provide funhouse-mirror (or waking-nightmare) reactions to what we see on cable news every morning.

Cherryh’s Foreigner novels have been appearing regularly for more than 20 years, but she is not the only marathoner. Charles Stross has been keeping two series going for more than a decade: the eight volumes of the Laundry (from 2002), and another eight (before revision and consolidation) of the Merchant Princes (from 2004). Both series had new entries in 2017, and both reflect the growing darkness that has worked its way into these already-dark worlds. Empire Games is the first-of-three in a new, next-generation movement in the Merchant Princes sequence, with the emphasis shifted from economics and politico-cultural change to matters of espionage and heartless, Cold-War-style covert operations in which very bad things are done by people who might only be scared stiff and desperate. Over in the more overtly terrifying world of the Laundry, The Delirium Brief continues to mine the metaphysical and political direness that lurks beneath the jokes about government bureaucracies. Both series continue to provide funhouse-mirror (or waking-nightmare) reactions to what we see on cable news every morning.

Ann Leckie’s Provenance is less part of a series than a common-setting book, using the far-future interstellar metacivilization that also includes the Imperial Radch sequence that established her reputation. It does, to be sure, share the deliberately defamiliarizing world- and character-building that made those first three books the topics of intense interest and conversation, but its scope is narrower and its issues are less fraught – or at least less dire. It shares with the Cherryh and MacDonald books a fascination with human relationships that have stretched and morphed to accommodate strange environments and situations: it is a novel of manners with big dollops of anthropology and xenology. (How does one ask an alien diplomat to tea?)

That stream of social-political-economic speculation runs through much of this year’s reading. Paul McAuley sets Austral in a future he sketched in an earlier story (is this the start of a series?) in which global warming is remaking the political and literal landscapes, reconfiguring geography, ecology, and class relations. Probably the most relentlessly focused sociopolitical novel I read this year is Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway, (a possible distant prequel to Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom), a heady Heinleinesque mix of technological speculation, dystopian warning, and libertarian revolutionary utopianism, spiced with Doctorow’s usual smart-ass humor and pauses for sermons on selected topics of interest or obsession.

Linda Nagata’s The Last Good Man would have fit right into previous years’ military-SF-rich summaries. It is a thematic but not narrative-sequence cousin of her Red trilogy, a continuation of her examination of the technological and political shape of soldiering in the near future. And since soldiering doesn’t happen in a vacuum, there is also a chilling picture of an international political environment in which the lines between states and private actors are blurred.

Linda Nagata’s The Last Good Man would have fit right into previous years’ military-SF-rich summaries. It is a thematic but not narrative-sequence cousin of her Red trilogy, a continuation of her examination of the technological and political shape of soldiering in the near future. And since soldiering doesn’t happen in a vacuum, there is also a chilling picture of an international political environment in which the lines between states and private actors are blurred.

I would set several of this year’s books next to the best I’ve encountered in my decades of reading the field. First among these is the late (and much lamented) Kit Reed’s final novel, Mormama, which took me back to the days of my dissertation research into the supernatural-fantastic, where it would have sat comfortably (if not comfortingly) in those places where the spooky-horrific and the abnormal-psychological intersect. I wish she had been able to hang on long enough to receive the praise she and this novel deserve.

Non-fiction does not quite fit into this discussion of novels, but Paul Kinkaid’s Iain M. Banks is an excellent examination of one of SF’s most significant recent writers and an implicit demonstration of what a series can accomplish. Banks’s Culture novels were not the first to deploy a vast common setting as a playground for ideas and adventures, but I would be surprised if they were not part of the inspiration for other writers (including some mentioned above) to stretch out in similar manner. Along a quite different axis of useful and enlightening, James Gunn’s Star-Begotten: A Life Lived in Science Fiction is an engaging professional/personal memoir of a formative period in American SF, when a kind of consensus future evolved as the biggest of common settings.

Since I have to pare final recommendations down to a subset, maybe put these at the top of the to-be-read list. But don’t stop there – let the TBR stack reach the ceiling.

Convergence, C.J. Cherryh

Walkaway, Cory Doctorow

Provenance, Ann Leckie

Luna: Wolf Moon, Ian MacDonald

Austral, Paul McAuley

The Last Good Man, Linda Nagata

Mormama, Kit Reed

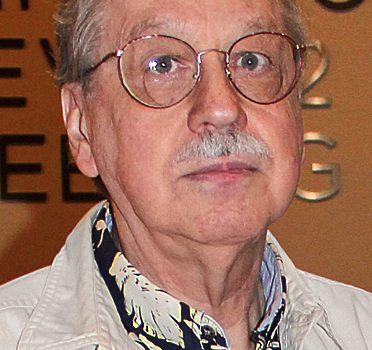

Russell Letson, Contributing Editor, is a not-quite-retired freelance writer living in St. Cloud, Minnesota. He has been loitering around the SF world since childhood and been writing about it since his long-ago grad school days. In between, he published a good bit of business-technology and music journalism. He is still working on a book about Hawaiian slack key guitar.

This article and more like it in the February 2018 issue of Locus.