Liz Bourke Reviews The Tiger’s Daughter by K. Arsenault Rivera

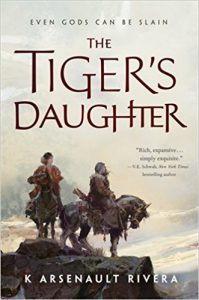

The Tiger’s Daughter, K. Arsenault Rivera (Tor 978-0-7653-9253-4, $15.99, 512pp, tp) October 2017. Cover art by Jaime Jones.

The Tiger’s Daughter, K. Arsenault Rivera (Tor 978-0-7653-9253-4, $15.99, 512pp, tp) October 2017. Cover art by Jaime Jones.

I read The Tiger’s Daughter, K. Arsenault Rivera’s debut novel, with very few expectations. I’d heard it was Mongol-inspired epic fantasy. That was about it – and the cover copy doesn’t exactly give one much more than that to go on.

This is, indeed, Mongol-inspired epic fantasy. It’s a coming-of-age story, and an epic romance, and an ambitious book that tells a complete story in itself – though there are two more volumes still to come. It’s also almost entirely about women: women as comrades, women as lifelong friends who want their daughters to have a similar bond, women as leaders. Women as lovers.

It seems inevitable that The Tiger’s Daughter will be compared to Elizabeth Bear’s Eternal Sky trilogy: Mongol-influenced epic fantasy isn’t all that widespread, and Range of Ghosts and its sequels are fresh in memory. Aside from the influences that inform the setting and the ambitions of the respective works, they have very little in common. They’re vastly different, both stylistically and thematically, which is great to see in works that draw so very deeply from similar real-world environmental and historical wells.

The Tiger’s Daughter gives us two fascinating protagonists in Shefali and O-Shizuka. O-Shizuka is the niece of an emperor, heir to a dynasty, most likely to succeed to the rulership of the Hokkaran empire, and she was born within a month of Shefali, daughter of the leader of the nomadic Qorin. Their mothers were comrades-in-arms, bonded in adversity beyond the Wall of Flowers where they fought a demon general and survived: Shefali’s mother the uncrowned leader of the Qorin, O-Shizuka’s a tradesman’s daughter who became the best swordsperson in the empire and married the emperor’s brother. They have been linked since birth, and friends since childhood, but when the novel opens, they have been separated for years. It will take the course of the book before we learn why.

The Tiger’s Daughter is told largely in epistolary fashion, in the form of a very long letter from Shefali to O-Shizuka – interspersed with very occasional interludes from O-Shizuka’s point of view, during O-Shizuka’s reading of the letter. Shefali has written a letter that is basically a memoir to O-Shizuka, so that (we learn later) O-Shizuka will have something to remember her by – a record of their life together if the thing that Shefali is about to do goes horribly wrong.

The novel begins in their early childhood, where they begin to navigate their roles and expectations and the connection that they both feel to each other. O-Shizuka is confident past the point of arrogance, preternaturally exceptional with calligraphy and with a sword, a driving, driven personality who can make flowers bloom out of season, believes she is a god, and possesses a strong sense of destiny. Shefali is much quieter, much less possessed by a conviction of her destiny – but her arrows never miss, she always knows her way in the dark, and she sees spirits and shadows. They spend time in each other’s worlds, Shefali in the palaces of the Hokkaran empire – where Hokkarans tend to despise the Qorin because of racism, a war in the not-too-distant past, and the Hokkaran view that the Qorin are uncivilised barbarians – and O-Shizuka on the steppes, after the deaths of her parents – deaths that her uncle the emperor essentially ordered – where she never quite entirely adjusts to Qorin ways.

On the steppes, Shefali and O-Shizuka fall in love. They keep their relationship secret, because while their love isn’t exactly forbidden, it’s not something the Hokkarans would approve of, and it’s not something that everyone’s enthusiastic about in Qorin culture, either. When the two young lovers set out in secret for the Wall of Flowers, spurred by O-Shizuka’s sense of destiny, a confrontation with a demon results in an unwelcome transformation for Shefali. Contaminated by tainted black blood, subject to monstrous urges and distressing visions, and the only person to survive this transformation – as far as she knows – with their will and volition intact, Shefali struggles to control herself. O-Shizuka vows to protect Shefali, and to do everything in her – in their combined – power to find a cure, but circumstances may not align in their favour: even a divine empress-in-waiting cannot protect her beloved from everything. Including both of their mistakes.

The Tiger’s Daughter is a lush and ambitious novel. It mostly succeeds, though like many epic romances involving adolescents, I’m not entirely convinced that the romance itself is entirely healthy for at least one of its participants. But I do believe in the characters, and in the case of the two protagonists, their deep attraction to each other, their mutual loyalty and attraction – and their personal flaws and failings, too. (I’m also really pleased with the characterisation of their mothers, complex people whom we see refracted only through the prism of – mostly – Shefali’s perception. They’re clearly badass operators in several different ways.)

One of the things that The Tiger’s Daughter attempts, more or less successfully, is to identify itself with a mythic register as well as a realistic one. It succeeds in this in part because of its epistolary frame: it’s a told story, and this personal view on an epic canvas recollects for me the logic and the emotional register of older epic poetry and literature. In its worldbuilding, though, in its approach to women, and in its approach to women in love, it is – thankfully – entirely modern.

Opinions may differ on whether the epistolary frame adds to the overall experience of the novel. Initially, the “You did this, I did that,” style of narrative made me feel somewhat displaced – as though I were witnessing some stunt-writing combination of viewpoint in the first and the second person, but the prose is rich and strong from the beginning, and I quickly grew accustomed. It’s hard now to imagine this story told in any other way.

It’s because The Tiger’s Daughter is an ambitious book that I can call it “more or less” successful. A less ambitious book, one that was attempting to do fewer things, might have succeeded at all of them at the cost of being far less interesting. But it is a vital, compelling, fascinating novel, despite a climax and conclusion that feels a little compressed. (I look forward to seeing how the sequel, due out next July, may change my feelings about how the conclusion here balances itself.)

I deeply enjoyed The Tiger’s Daughter. It surprised and delighted me. It’s an extremely promising debut, thoughtful and assured. Now I’m really looking forward to reading more of K. Arsenault Rivera’s work.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, her Patreon, or Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.

This review and more like it in the December 2017 issue of Locus.