Russell Letson reviews Star-Begotten: A Life Lived in Science Fiction by James Gunn

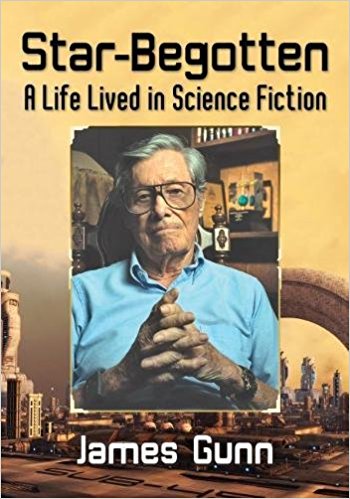

Star-Begotten: A Life Lived in Science Fiction, James Gunn (McFarland 978-1-4766-7026-3, $25.00, 209pp, tp) November 2017. Cover photo by Jason Dailey.

I hope I might be excused for injecting personal notes into a review of James Gunn’s autobiography, Star-Begotten: A Life Lived in Science Fiction. As I read it, I couldn’t help noticing how many times and in how many ways my life in SF was affected by Gunn’s work as writer, editor, and academic activist. One of my earliest book purchases, around 1957, was the Ace paperback (Double Size! 35 cents!) of Star Bridge, the space opera he co-wrote with Jack Williamson. (I still have a double-autographed copy of a later Ace printing, the original having long since succumbed to pulp rot.) Before that, I had listened to the 1956 X Minus One radio adaptation of his short story ‘‘The Cave of Night’’. (It’s still available online.) Years later, the third volume of The Road to Science Fiction was one of the reliable anthologies for my SF course, and a few years after that I wrote a dozen entries for The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction that he edited. By that time, Gunn had been president of both the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America and the Science Fiction Research Association, started the Center for the Study of Science Fiction at the University of Kansas, and worked for years as a promoter of the study and practice of science fiction.

I hope I might be excused for injecting personal notes into a review of James Gunn’s autobiography, Star-Begotten: A Life Lived in Science Fiction. As I read it, I couldn’t help noticing how many times and in how many ways my life in SF was affected by Gunn’s work as writer, editor, and academic activist. One of my earliest book purchases, around 1957, was the Ace paperback (Double Size! 35 cents!) of Star Bridge, the space opera he co-wrote with Jack Williamson. (I still have a double-autographed copy of a later Ace printing, the original having long since succumbed to pulp rot.) Before that, I had listened to the 1956 X Minus One radio adaptation of his short story ‘‘The Cave of Night’’. (It’s still available online.) Years later, the third volume of The Road to Science Fiction was one of the reliable anthologies for my SF course, and a few years after that I wrote a dozen entries for The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction that he edited. By that time, Gunn had been president of both the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America and the Science Fiction Research Association, started the Center for the Study of Science Fiction at the University of Kansas, and worked for years as a promoter of the study and practice of science fiction.

He is also of my parents’ generation, so the first two chapters of his memoir, about growing up through the Depression and WWII, is full of echoes of and variations on the family stories I grew up with – but the audience for this book should be broader than the geezer or even the long-term-science-fiction-fan demographics. It offers a view of Gunn’s long career and of the culture that surrounded it, joining a shelf of biographies, autobiographies, memoirs, and histories that describe the world that produced American SF: books by or about Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, L. Sprague de Camp, Harry Harrison, Robert A. Heinlein, Damon Knight, Judith Merril, Fred Pohl, Robert Silverberg, Jack Vance, and Jack Williamson.

But about James Gunn himself: despite the romantic tone of the book’s title (taken from an H.G. Wells novel), the voice and persona in this memoir is distinctly Midwestern, not so much aw-shucks (Gunn is not averse to taking some pride in his accomplishments) as low-key and matter-of-fact. The subtitle, though, is right on the money: the through-lines of Gunn’s adult life have been science fiction and writing, and especially writing science fiction. The early parts of his story form a familiar pattern: he was an omnivorous and enthusiastic reader from childhood onward, including Tarzan books, hero pulps shared with his father (Doc Savage, The Shadow), and inevitably SF and fantasy. He knew that he wanted to be a writer, though it was not SF but radio, journalism, and theater that attracted his first efforts in high school and college. But once he sold his first story to Thrilling Wonder Stories while in grad school at the University of Kansas in 1949, he was on his way, working his way up the magazine hierarchy to Galaxy and Astounding. He had day jobs – a useful period as a junior editor at Western Printing & Lithographing (the company behind Dell books and magazines back then) and eventually a series of writing, editing, and public-relations positions at the University – but he never stopped writing and publishing SF. W hen he got out of the university’s back-office gigs and started teaching, his focus was on science fiction as a literary genre and a writing discipline.

The first quarter of the book, however, is quite personal, and it accounts for the voice and tone of the whole. Gunn’s stable childhood and solid public education prepared him for the other connection that defined him: with the University of Kansas, where he got his degrees, learned the craft of journalism, met his wife, raised his family, and worked for most of his life. After his return from the Navy in 1947 he never left Kansas for very long (the year and a half with Western Printing was the longest stretch away), and that mid-continent rootedness characterizes him as much as his devotion to the hopeful visions of science fiction.

The university jobs allowed him to write without worrying as much about the state of the fiction market (of which, nevertheless, he was always keenly aware), and the university later provided institutional support for projects such as annual workshops on the teaching and writing of SF and a home for the Campbell and Sturgeon awards. The middle stretch of the book follows his university and writing careers and charts his engagement with science fiction’s professional-social culture. Starting in 1952, he attended world conventions, where he met fellow writers: at the 1952 Chicon it was Clifford Simak, Mack Reynolds, Jack Williamson, and Frederik Pohl (who was his first agent). He also recounts his progress as a professional, setting a regular work schedule (‘‘writing was a normal human activity, and writers shouldn’t wait for inspiration or require special circumstances’’), keeping track of story ideas on index cards, and also tracking his income and activities – one ten-page stretch includes submission histories, word rates, payments, and eventual publication venues of ten of his early stories. He was from the start an organized, patient, and persistent worker – and a practical one, as indicated by the decision he came to after the toil and relatively modest remuneration of writing This Fortress World and co-writing Star Bridge:

I came up with what later became known among my students as Gunn’s Law: Sell it twice. I decided that when I had future novel-length ideas, I would divide them into novellas or novelettes that I could publish in magazines and then combine into novels. And that’s what I did for the next half-dozen books….

The professional life is only part of a full life, though, and Gunn includes memories of his courting and marriage, the births of his sons, the houses they lived in, their neighbors, the succession of university jobs he held, the bridge tournaments he played in with his father, the loss of his older son and his wife Jane – a wealth of domestic detail that says as much about the man as his work does. And since those early-1950s Worldcons, his involvement with the SF culture has been extensive – he seems to have met everyone and worked with most of them via SFRA, SFWA, university-based conferences, or publishing projects. The book is studded with encounters with the field’s editors, agents, and publishers, as well as the expected writers. Appendix A includes memories of Theodore Sturgeon (on the occasion of the donation of the Sturgeon papers to the University collections) and a series of generous, affectionate extended appreciations of Fred Pohl, Damon Knight, Harry Harrison, Clifford Simak, and John Brunner, along with a tribute to Murray Leinster (the only one Gunn did not know personally).

Given Gunn’s long and varied career, his autobiography – particularly one with such a detailed account of his professional activities – should be a significant source for scholars. An index is promised for the finished book, but what is also needed is a more complete dating and venue identification of the various embedded documents that punctuate Gunn’s narrative, sometimes repeating and sometimes expanding on parts of the story: high school and university 50th-reunion addresses, articles about speaking tours (one from Locus), and several award-acceptance speeches (the SFWA Grand Master acceptance is dated in its title).

This book makes an interesting companion to his friend Harry Harrison’s posthumous memoir (Harry Harrison! Harry Harrison!), since the two writers’ careers occupy the same period and exhibit some of the same diversity of activities beyond the writing of stories and novels. The lives and personalities, of course, differ a good bit: Harrison the colorful bohemian wanderer versus Gunn the low-key, lifelong Kansan. But both lives really were lived in and through the written word and the world of science fiction, and their books are appropriate neighbors on that shelf of SF memoirs.

Russell Letson, Contributing Editor, is a not-quite-retired freelance writer living in St. Cloud, Minnesota. He has been loitering around the SF world since childhood and been writing about it since his long-ago grad school days. In between, he published a good bit of business-technology and music journalism. He is still working on a book about Hawaiian slack key guitar.