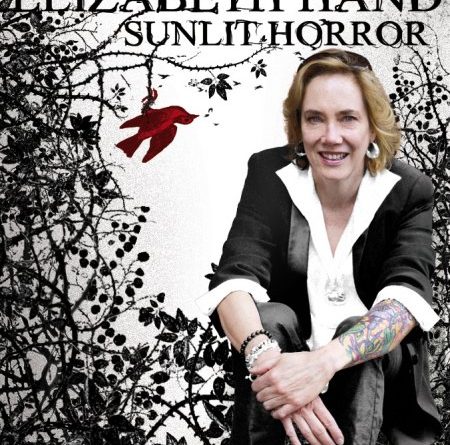

Elizabeth Hand: Sunlit Horror

Elizabeth Hand was born on March 29, 1957 in San Diego CA and grew up in New York State. She moved to Washington DC in 1975 to study drama at Catholic University. In 1979, during college, she began working at the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, and was an archival researcher there until 1986. During that time she was expelled from college, but returned after two years and received her degree in cultural anthropology in 1984. She became a full-time writer in 1987, publishing first story ‘‘Prince of Flowers’’ in 1988. She moved to Maine in 1988 with writer Richard Grant, whom she met at a writing workshop. She and Grant lived together for eight years, though they never married; they had two children, now adults.

Hand excels at supernatural horror, SF, fantasy, and mainstream fiction, and has produced notable work in all those genres. Debut novel Winterlong (1990) started an SF series that includes Aestival Tide (1992) and Icarus Descending (1993). Contemporary fantasy Waking the Moon (1994) won the James Tiptree, Jr. Award and a Mythopoeic Award. Science fantasy Glimmering appeared in 1997, contemporary fantasy Black Light in 1999, historical fantasy Mortal Love (2004), and time-slip novel Radiant Days in 2012. Shirley Jackson Award winner Generation Loss (2007) began the Cass Neary series of crime novels with some supernatural elements, which also includes Available Dark (2012) and the forthcoming Hard Light. Her latest book is short novel Wylding Hall.

Hand is adept at short fiction, with work appearing in major magazines and anthologies. The title story of collection Last Summer at Mars Hill (1998) won World Fantasy and Nebula Awards. Other collections include World Fantasy Award winner Bibliomancy (2003), Saffron and Brimstone: Strange Stories (2006), and Errantry (2012). Notable individual works include ‘‘The Boy in the Tree’’ (1989), ‘‘Snow on Sugar Mountain’’ (1991), ‘‘In the Month of Athyr’’ (1992), ‘‘The Erl-King’’ (1993), ‘‘Chip Crockett’s Christmas Carol’’ (2000), and ‘‘The Least Trumps’’ (2002). ‘‘Cleopatra Brimstone’’ (2001) and ‘‘Pavane for a Prince of the Air’’ (2002) both won International Horror Guild Awards, ‘‘Echo’’ (2005) won a Nebula Award, novella Illyria (2007) won a World Fantasy Award, ‘‘The Maiden Flight of McCauley’s Bellerophon’’ (2010) was a World Fantasy Award winner and Hugo and Sturgeon Award finalist, and ‘‘Near Zennor’’ (2012) was a World Fantasy Award finalist and won a Shirley Jackson Award.

She has also written movie and TV novelizations, including several Star Wars YA novels. She reviews books for numerous publications, including the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times. She divides her time between Maine and London with her partner, UK critic John Clute.

Excerpts from the interview:

“I had several unsuccessful attempts at writing Wylding Hall – it kept morphing from one thing to another. I was coming back from a flight, I was very jetlagged, and I’d been reading the umpteenth bio of Nick Drake on the plane over. I got back home to London and was lying in bed. I couldn’t sleep, and all of the sudden, I sort of heard all these voices telling this story, and thought, ‘Oh, I could do this like an imaginary biopic. Like a behind-the-music sort of thing.’

‘‘The story dovetails with the history of the band Fairport Convention, which had a tragic accident when they were all quite young – I think Richard Thompson was 17. They were coming back from a gig at two or three in the morning, and their van went off the road. Their drummer was killed, Thompson’s girlfriend was killed, and the others were very seriously injured, some of them in the hospital for months. A few months later their manager/producer, Joe Boyd, found a house in this place called Farley Chamberlayne, a little town in Herefordshire, and rented it for them for the summer. He said, ‘Look, just go here and recuperate from the trauma. Go see what happens.’ They wrote the material that became their groundbreaking album Liege & Lief. The characters in Wylding Hall are not in any way analogous to the members of Fairport Convention, but I took their story as a jumping-off point: what would happen? They were all really young, and it was this charged moment in cultural history – read Electric Eden, Rob Young’s wonderful book about British folk music. His account begins in the late 19th century, and incorporates Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood – it ties in all of these elements of our culture, our speculative fiction culture, as well as film, like The Wicker Man. He has a century-long survey – longer than that – of this visionary music. Kind of like Greil Marcus’s book Mystery Train, about ‘the old, weird America.’ I read Rob Young’s book three times, and I thought, ‘I can use this material.’

‘‘What happens if you take these people, at this moment, put them in a big creepy house, and take an old creepy English folk song and bring it to life? Have something unresolved happen, with the story being retold when all of the people who were teenagers at the time are now middle-aged. You get that Rashomon effect – who do you believe? Who saw what when? Nobody quite saw the same thing.

‘‘I thought that was a cool way of telling a supernatural story. Sort of like, when you hear a ghost story when you’re a kid, at a campfire or a sleepover, and later you’re at someone else’s sleepover, and another kid tells the same story, but the details are different. The essence of the story is the same – something scary happens – but it morphs.

‘‘Just because you’re young and really stoned and in a weird creepy place, that doesn’t mean something really weird and creepy isn’t actually happening. I like the notion, too, that you don’t know you’ve seen a ghost until afterward. There’s an Edith Wharton story called ‘Afterward’. Somebody saw something, or they didn’t see something, and then later on they put it together and realized they had seen a ghost. I wanted to play with that, the idea of sunlit horror. Most of Wylding Hall takes place during the day.”

…

‘‘I wanted the story to drop off at the end. I know some readers had issues with that – they wanted more. But I wanted it to have an unresolved ending – that was deliberate on my part. I wanted something that would have more of the impact of an actual lived experience. If you were to experience something strange like that, it would not be resolved. You would not know what happened. It would not get tied up neatly, like, ‘Oh, it was a visitation from the goddess, or it was this ghost.’ You wouldn’t know what it was. In fiction we want things resolved, and I know it can be unsatisfying for things to be unresolved, but I think that there’s room for things being open-ended. I wanted, deliberately, at the end, to have every single person in the band think something different happened. That’s what they believed, and the reader can decide for herself what she thinks happened.”

…

‘‘Hard Light is the third Cass Neary book, and I’ve just been contracted to do a fourth. Hard Light will be out early next year. It’s sort of a transitional novel. The one that comes after it, the one I’m working on now, is called The Book of Lamps and Banners. That is a great title, I’ve got to say. I’ve had that arrow in my quiver for ten years, and I finally thought, ‘I know where I can use it.’

‘‘With Hard Light, I found that I really love writing these books. I wanted to keep within the noir mode, but I also wanted to draw in more of the subtle, underplayed, quasi-supernatural elements. Although there’s not really a supernatural element in Hard Light, per se, there is a flicker of the supernatural in Generation Loss, that recurs in Available Dark, and in all of the books. With this one I was able to again make use of some – not necessarily British folklore, but British prehistory. It starts off in London, and then takes a U-turn and goes to West Penwith and Cornwall, which is a beautifully eerie, atmospheric place. With Hard Light, more than the previous two books, I was able to draw on earlier books like Waking the Moon, or Black Light, or Mortal Love – novels that are set in our world, with an eruption of the supernatural. The supernatural doesn’t quite erupt in the Cass books, but I want there to be a feeling that it could, that it’s right under the surface. That was really fun. I don’t know if ‘liberating’ is the right word, but it was enjoyable to write it and be able to incorporate some of that material.”

Read the complete interview in the October 2015 issue of Locus Magazine. Interview design by Francesca Myman.