|

|

REVIEWS : Films

earlier film & opera reviews: Watchmen (Waldrop & Person) Coraline (Gary Westfahl) Futurama DVDs (Waldrop & Person) The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (Gary Westfahl) 1958 (Gary Westfahl) The Day the Earth Stood Still (Gary Westfahl) Blindness (Gary Westfahl) The Fly: the opera (Mark R. Kelly) Fly Me to the Moon (Gary Westfahl) The Dark Knight (Gary Westfahl) Journey to the Center of the Earth (Gary Westfahl) Wall-E (Gary Westfahl) Dreams with Sharp Teeth (Gary Westfahl) Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (Waldrop & Person) - 2008 Reviews Archive - Index to Movies Reviewed on Locus Online Index by Reviewers |

5 April 2009

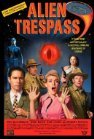

Directed by R.W. Goodwin Written by James Swift and Steven P. Fisher, story; screenplay by Fisher Starring Eric McCormack, Jenni Baird, Robert Patrick, Dan Lauria, Aaron Brooks, Sarah Smyth, Andrew Dunbar, and Jody Thompson Official Website: Alien Trespass / The Invasion Begins April 3! If told that their film was an early contender to be the best science fiction film of 2009, the makers of Alien Trespass would surely respond that that was never their goal. Rather, what writers James Swift and Steven P. Fisher and director R. W. Goodwin clearly set out to do in 2007, fifty years after the fact, was to make the best science fiction film of 1957. And the highest compliment one can pay to their efforts is that they have brilliantly succeeded. To be sure, many other filmmakers have endeavored to emulate the science fiction films of the 1950s, so much so that the era remains the most important and influential decade in the genre's history. But they usually get it wrong in one of two ways — either by drifting into deliberate satire, or by striving to make everything bigger and better. These filmmakers, in contrast, were determined to precisely match both the earnestness, and the limitations, of those beloved classic movies. Indeed, the conceit of the film, as revealed in an introductory newsreel purportedly reporting the news of 1957, is that Alien Trespass was actually made in 1957 and then suppressed due to a feud between its star Eric McCormack (the real name of the film's star) and producer Louis Q. Goldstone (mixing the names of movie moguls Louis B. Mayer and Samuel Goldwyn). As one would expect in this case, the filmmakers brought to this project an encyclopedic knowledge of 1950s science fiction films, as various references indicate. True, I can recall no cinematic precursor that exactly replicates its story line — an alien law enforcement officer, escorting a dangerous alien prisoner, is forced to land on Earth when its captive damages his spacecraft and then must take on human form to track down and recapture the creature after it escaped during the crash landing (though filmmakers may have been borrowing from the somewhat similar plot of Hal Clement's 1950 novel Needle). However, as suggested by the film's working title, It Came from Beyond Space, some aspects of the story are reminiscent of It Came from Outer Space (1953), wherein another alien in a damaged spacecraft lands, seeks human assistance, and eventually repairs his ship and departs, while the spaceship itself — a flying saucer — looks exactly like the one in The Day the Earth Came Still (1951), right down to the descending ramp that its pilot exits from. Also, the humanoid alien, covered in silver, may resemble Gort, but he is shot at and wounded by a trigger-happy youth in uniform, like Klaatu; the alien's farewell gesture mirrors that of Klaatu; and the film's soundtrack features the eerie whine of a theremin, heard in The Day the Earth Stood Still and other films of its era (the credits specifically credit a theremin player, confirming that the now-obscure instrument was actually employed). The bedroom of a little boy — criticized because he loves that "science fiction junk" — has posters of Destination Moon (1950) and The Man from Planet X (1951) on the wall, and when one woman speaks of "killers from space," she is referencing another 1950s science fiction film, the 1954 Peter Graves epic of that name. The sinister alien — a one-eyed purple creature called the Ghota (Jovan Nenadic) — seems a blending of the monsters in It Came from Outer Space, It Conquered the World (1956), and The Crawling Eye (1958). And the film's virtuous teenagers — Cody (Aaron Brooks), Dick (Andrew Dunbar), and Penny (Sarah Smyth) — unable to convince dimwitted adults that a strange monster is on the loose, have obvious predecessors in Invasion of the Saucer Men (1957) and other late-1950s films that employed teenagers as protagonists. One of those films, of course, was The Blob (1958), which this film most prominently pays homage to. In the first place, the tacky diner where much of the film's action occurs recalls the similar restaurant in The Blob (its name, Lucky's Diner, presumably pays tribute to Lauren Taylor "Lucky" Swift, given "Special Thanks" in the closing credits and best known as the producer of an earlier cult classic, Trail of the Screaming Forehead [2007], which included a cameo appearance by this film's co-author, James Swift). More interestingly, a scene near the end of this film replicates the earlier film's most striking sequence. Creating a movie to be shown to people sitting in theatres, the 1958 filmmakers were truly ingenious to have their immense Blob climactically attack people sitting in a movie theatre. Here, theatergoers are watching precisely that scene from The Blob when their own theatre is invaded by their very own Blob. And since the 1958 film was notoriously filmed in Pennsylvania, that may explain why the introductory newsreel features a Santa Claus in a flying saucer who is paying a visit to Pennsylvania. In a small way, Alien Trespass also acknowledges that 1950s science fiction films often featured shaky scientific knowledge. In the opening scenes of the film, when everyone believes that the downed flying saucer was actually a large rock from space, learned astronomer Ted Lewis (McCormack) refers to it as a "meteoroid" while the ignorant policeman Vernon (Robert Patrick) dismisses it as a "meteor." Of course, both men are wrong, since a meteoroid is a rock traveling through space, a meteor is a rock that burns up in our atmosphere, and a rock that actually hits Earth's surface is a meteorite. The kindly alien is also given to outbursts of meaningless pseudo-scientific jargon, though he does come up with a charming way to describe the human phenomenon of romantic love — "hormonal polarity." In addition to its resonances with the stories of 1950s science fiction films, Alien Trespass commands attention because it so carefully mimics the visual style of those films. The colors of the film are a bit garish and not quite realistic, reflecting the imperfect technology then employed by penny-pinching producers; when filming characters driving in cars, the scenery in their windows is provided by rear-view projection, the standard procedure in films of that era; and painstaking efforts were made to ensure that all of machinery and props were authentically of the 1950s, including the Electrolux vacuum cleaner, a jukebox, a Polaroid instant camera, and several classic cars. (In fact, the credits include a "Vintage Mechanic" whose job on the set was presumably to keep all of those old cars running smoothly.) In the entire film, I only spotted one anachronism: in the newsreel segment on the Pioneer space probe, the countdown to zero was depicted as an electronic display, when the technology of the time would have instead employed black numbers on a white wheel, observed turning into position one at a time through an opening in the machine. There is also one understated sign of contemporary attitudes: throughout the film, as was commonplace in 1950s films, characters occasionally smoke cigarettes, and astronomy professor Ted Lewis (McCormack), in keeping with the stereotypes of the day, wears glasses and incessantly smokes a pipe. When taken over by the alien, however, Lewis does not wear his glasses and never smokes. At the end of the film, when Lewis regains control of his body, the alien makes a special trip to return the glasses to the professor, but he pointedly declines to return the pipe. Manifestly, drawing upon superior scientific knowledge unavailable to filmmakers in the 1950s, the alien is advising Lewis to stop smoking. The film's acting also commands attention. I will admit that in the film's opening scenes, which may also have been filmed first, one sensed that the actors playing Lewis and his wife Lana (Judy Thompson) were deliberately trying to act badly, generating a brief fear that the film would descend into parody. But as the film gets into its rhythm, the cast manages to replicate the manner of acting that we would expect to observe in a 1950s science fiction film — namely, weak to moderately-talented actors doing the very best that they can to seem sincere. But McCormack provides the film's standout performance. In the scenes after Lewis's body is taken over by the alien policeman Urp, I was reminded of the way that Paul Birch, in Not of This Earth (1956), subtly conveyed his alien nature by using a curious two-finger gesture to turn on a light switch. McCormack as an alien displays similarly incongruous behavior. For example, staring puzzledly at a glass of orange juice, he picks up the glass by grasping the rim between his thumb and forefinger; he deliberately turns a salt shaker upside down and watches the salt pour out (the first instance of the recurring motif of characters spilling salt, explaining their bad luck in being threatening by a murderous monster and anticipating the revelation that salt can serve as a weapon against the monster); and later, when he gets out of a car, he leaves the door standing wide open instead of automatically closing it behind him in the way that any human driver would. Yet one must also praise the more conventional work of Jenni Baird, who as Tammy, a frustrated artist working as one of the diner's waitresses who becomes attached to Urp-controlling-Lewis, articulates the central message of the film. Near the end of the film, the only thing that can prevent Urp from successfully completing his mission is a mob of gun-wielding citizens led by Dawson, the police chief (Dan Lauria). Tammy implausibly drives them away with an impassioned speech about our need to rise above petty concerns in this "big universe" we live in and to gratefully support "this traveler from another world" who has worked so hard to benefit humanity. At this moment, we are suddenly reminded that there are legitimate reasons to value and cherish the science fiction films of the 1950s that in so many other respects appear to merit only scorn. For in their own naïve and clumsy way, these films were saying important things. They validated youth and novelty over age and tradition; they preached tolerance and respect for beings that might seem strange to us; they encouraged people to abandon parochial narrow-mindedness, adopt a broad, cosmic perspective, and embrace grand ambitions. Even before Tammy's speech, the film, in ways that perfectly accord with the conventions of 1950s science fiction movies, celebrates such virtues. Time and again in the film, the kids are right and the adults are wrong. We know that Vernon is a complete creep when, after Tammy rejects his crude passes, he intimates that she must be a lesbian, a prejudicial attitude clearly being condemned. In one scene at the diner, an African-American worker (Dee Jay Jackson) is silently accepted by everyone as a participant in the conversation, reminding us that there were 1950s science fiction films like The World, the Flesh, and the Devil (1959) that attacked racism. And as Urp predicts, Tammy finally resolves to leave her dead-end job and move to Sausalito, where she will become a member of its artists' community — anticipating the more independent and fulfilling lifestyles that the children who watched these 1950s films would seek out as young adults during the swinging sixties. In contrast, despite their grandeur and polish, the prestigious and award-winning films of the 1950s — the Douglas Sirk melodramas, the biblical epics, the Cinemascope westerns, the dreary social commentaries, etc., etc. — really had very little of importance to say, which is why they have largely been forgotten. If science fiction films proved to be the long-lasting Mustangs of their day, such major films were its ephemeral Edsels (the short-lived Ford model explicitly mocked in the film). It makes perfect sense, then, that someone in the early twenty-first century would seek to replicate the 1950s science fiction film, while no one at all is endeavoring to revive any of the decade's other distinctive genres. And in this respect, Alien Trespass is sending another important message to the contemporary creators of science fiction films. Today, the science fiction blockbusters getting most of the attention may have enormous budgets, spectacular special effects, first-rate talents in all departments, and crowd-pleasing, pseudo-profound endorsements of conventional wisdom, but in most respects these films seem to be as empty as, say, The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) or Peyton Place (1957), and it is impossible to imagine anyone in the year 2057 bothering to pay homage to them. To make truly memorable films, Alien Trespass suggests that science fiction must go back to the future and follow the simple agenda of 1950s science fiction films: small budgets, big ideas. In doing so, however, filmmakers do not necessarily need to precisely mimic the tropes and style of their predecessors in the manner of Swift, Fisher, and Goodwin; for while watching this film I was reminded of another memorable film of recent years, the obscure, direct-to-DVD release Jerome Bixby's The Man from Earth (2007), which makes no effort to emulate 1950s films but effectively manages to fascinate viewers, despite miniscule resources and not a single special effect, with a long, thought-provoking conversation. These are the sorts of films that members of the science fiction community should be seeking out and supporting. And so, even though it is unlikely to work its way into wide release, I would urge everyone reading this to somehow find and watch Alien Trespass, to be fruitfully reminded of a time when science fiction films were small productions that enlightened their viewers about our big universe. | |

|

|

| © 2009 by Locus Publications. All rights reserved. |