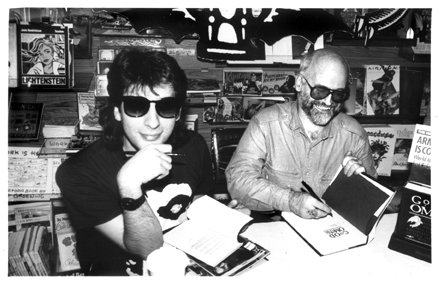

Pratchett & Gaiman: The Double Act

Neil Gaiman: "The first radio interview we did in New York, the interviewer was asking us 'Who is Agnes Nutter? What is her history? Is Armageddon happening?" and so on and so forth. After a while, we twigged he hadn't realized this was fiction. He thought he'd been given two kooks who'd come across these old prophecies and were predicting that the world was going to be ending."

Terry Pratchett: "Once we realized, it was great fun. We could take over the interview, since we knew he didn't know enough to stop us."

NG: "And at that point, we just did the double act."

NG: "We're working on seeing how many smart-alec answers we can come up with when people ask us how we collaborated."

TP: "I wrote all the words, and Neil assembled them into certain meaningful patterns... What it wasn't was a case of one guy getting 2/3 of the money and the other guy doing 3/4 of the work."

NG: "It wasn't, somebody writes a three-page synopsis, and then somebody else writes a whole novel and gets their name small on the bottom."

TP: "That isn't how we did it, mainly because our egos were fighting one another the whole time, and we were trying to grab the best bits from one another."

NG: "We both have egos the size of planetary cores."

TP: "Probably the most significant change which you must have noticed [between the British and American editions] is the names get the other way 'round. They're the wrong way 'round on the American edition [where Gaiman is listed first] --"

NG: "They're the wrong way 'round on the English edition."

TP: "Both of us are prepared to admit the other guy could tackle our subject. Neil could write a 'Discworld' book, I could do a 'Sandman' comic. He wouldn't do a good 'Discworld' book and I wouldn't do a good 'Sandman' comic, but --"

NG: "-- we're the only people we know who could even attempt it."

TP: "I have to say there's a rider there. I don't think either of us has that particular bit of magic, if that's what it is, that the other guy puts into the work, but in terms of understanding the mechanisms of how you do it, I think we do."

NG: "There's a level on which we seem to share a communal undermind, in terms of what we've read, what we bring to it."

TP: "In fact, people that have read a lot of the 'Discworld' books and a lot of the 'Sandman' comics will actually find, for example, Neil put into one of the 'Sandman' comics a phrase lifted out of a 'Discworld' book. I spotted it in a shop and said, 'You bastard! You pinched my sentence. Everyone liked that line, and you pinched it.'"

So how did the collaboration on Good Omens begin?

TP: "Neil wrote several thousand words a couple of years ago, which was part of the main plot of Good Omens."

NG: "I didn't know what happened next, so I put it aside and I showed it to Terry. One day I got this phone call from Terry, saying 'Remember that plot? I know what happens next. Do you want to collaborate on it, or do you want to sell it to me?' And I said, 'I'll collaborate, please.'"

TP: "Best decision he ever made! I didn't want to see a good idea vanish. It turned out, more and more things kind of accreted 'round it as the book was written. Also, Neil went and lost them anyway, so it all had to be retyped."

NG: "I'd lost it on disk, so I gave him a hard copy, which meant he had to type it in. He kept changing it."

TP: "I changed it so I could make the next bit work. The thing kind of jerked forward quite quickly, as both of us raced one another to the next good bit, so we would have an excuse to do it. Both of us cornered certain plot themes which we stuck to like glue."

NG: "Like the reluctance with which I handed over the Four Horsepersons of the Apocalypse to Terry when they got to the airbase."

TP: "I seldom let Neil touch any of the bits involving Adam Young himself."

NG: "When we got to roughly the end, we could actually see which characters we hadn't written. So we made a point of going in and writing at least one or two scenes with any of the characters that up until then we hadn't written."

TP: "Insofar as there's any pattern at all, we worked out what the themes were and then we each took a theme and wove that particular strand."

NG: "The other pattern, of course, was that you'd do your writing in the morning and I'd do mine late at night."

TP: "Which means there was always someone, somewhere, physically writing Good Omens."

NG: "It took nine weeks."

TP: "We look upon Good Omens as a summer job. The first draft for nine weeks was sheer, unadulterated fun. Then there were nine months of rehashing, then there was the auction."

NG: "When you have situations when you've got three agents, five publishers, all that kind of stuff...."

TP: "Our friendship survived only because we had other people to shout at. So I could say, 'Take that, you bastard!' and hit his agent."

NG: "One thing Terry taught me, when we were writing the book together, was how not to do it. Too many funny books fail because people throw every single joke they can think of in, and have an awful lot of fun, and eventually it just becomes a collection of gags."

TP: "The big problem you face if you're working collaboratively on a funny book is that you start with a gag and it's great, it's very amusing, but with the two of you discussing it, eventually it's not good anymore. It's an old gag from your point of view, so you avoid it and you take it further and further. What you're putting in is a kind of specialized humor for people who work with humor. There's an old phrase, 'Good enough for folk music.' As you work, you have to stand back and say, 'Never mind whether we are bored with this particular gag, is the reader going to be bored with it, coming to it fresh?'"

NG: "One of the great things about humor is, you can slip things past people with humor, you can use it as a sweetener. So you can actually tell them things, give them messages, get terribly, terribly serious and terribly, terribly dark, and because there are jokes in there, they'll go along with you, and they'll travel a lot further along with you than they would otherwise."

TP: "The book has got its gags, and we really enjoyed doing those, but the core of the book is where Adam Young has to decide whether to fulfill his destiny and become the Antichrist over the smoking remains of the Earth, or to decide not to. He's got a choice, and so have we. So to that extent I suppose he does symbolize humanity."

TP: "Bear in mind that we wrote Good Omens while the Salman Rushdie affair was really just coming to a boil in the UK. But no one's going to go around burning copies of Good Omens, no on would think about that."

NG: "Yet everything is blasphemous. Technically speaking, Good Omens is blasphemous against religious order, as blasphemous as you can get. And Gollancz have just bunged it in for the big religious award in the UK, which we find very strange. They actually asked the archbishop of Canterbury to send vicars 'round to have serious tea with us."

Future plans?

TP: "There's always another 'Discworld' book. The way I look at it, if I don't have to force them -- if I want to do them, if publishers want me to do them, and readers want me to do them, I can go on doing them. The current 'Discworld' book, Moving Pictures, is about the 'Disworld' film industry. There are so many cinema industry gags that you can do, the problem was cutting ones out. There's a natural attraction to the subject for fantasy writers, because movies are not real in any case.

"Then, in Reaper Man [the next 'Discworld' novel'], you find out how shopping malls breed, and what the purpose of a shopping mall actually is. You're familiar with the idea of 'metalife,' the idea that cities are living things. Shopping malls are city predators. They spring up around the outside like starfish on a reef, and they draw the life out, the people, so the city starts to die in the middle. This is actually a minor plot in Reaper Man.

"There is no shortage of ideas for 'Discworld' books. It's probably going to slow down a wee bit, because I've got some other stuff planned. I'm going to do another children's book. There's my big science fiction novel I've been trying to do for three years, and I'm going to have to get that one finished now. I've finished the first draft for the script for the film of Mort, which may or may not happen. And finally, I'm toying with the idea of a comic, but it's got nothing to do with 'Discworld'. It's called 'Stalin' and it's what would happen if Superman landed in Russia in 1904. The direct translation of the word 'Stalin' is 'man of steel.' I'm not intending it to be a particularly funny comic. It has to be tragic, not because that's the fashion for superheroes, but because when you consider Russian history, it is tragic."

NG: "What am I doing next? I'm still writing 'Sandman'. The Rolling Stone plug for 'Sandman' in their 'hot' issue last year, combined with the actual graphic novel collection, has done wonders for increasing the readership. The first eight will also be collected by DC, which will mean a problem with how we number that collection, having brought out the second collection first. 'Sandman' is going to keep going for about another two years. 'Miracle Man' is great fun. I'm doing it roughly bi-monthly for Eclipse. It's utopian SF, and it's getting stranger and stranger, because I don't even have the commercial constraints that I have in 'Sandman'. The next one is done as if Andy Warhol were doing comics. Then I'm doing a horror comic series which will be appearing in Taboo, about Sweeney Todd. 'Signal to Noise', a graphic series I did with Dave McKean, which was serialized in English trendy style magazine The Face, has just been bought in a two-book deal by Gollancz. We'll be expanding it slightly, and that will be coming out early in the launch of their new graphic novel line. And I've started work on a fantasy novel, which won't be funny and may not even be very scary. It's called Wall."

TP: "We've both got lots of stuff to do. So if you allow time for eating and sleeping, Good Omens 2 doesn’t seem to fit in there very well."

NG: "It will probably never happen. We actually know how it would go. We know the theme -- '668, The Neighbor of the Beast'."

TP: "We even know some of the main characters in it. But there's a huge difference between sittin' there chattin' away, saying, 'Hey, we could do this, we could do that,' and actually physically getting down and doing it all again. One problem is, we've been saying it fliply, but it's almost true these days, we're not on the same continent for nine weeks at a time anymore."