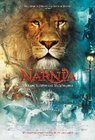

The Chronicles of Narnia:

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe

a review by Cynthia Ward

Directed by Andrew Adamson

Screenplay by Ann Peacock, Andrew Adamson, Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely, based on the novel by C.S. Lewis

Starring Tilda Swinton, Georgie Henley, Skandar Keynes, William Moseley, Anna Popplewell, and the voices of Liam Neeson, Ray Winstone, Dawn French, and Rupert Everett

A Preliminary Conversation

Scouting Christmas gifts at my town's new wineshop, I found myself discussing fantasy and science fiction with the co-owner's daughter's partner. Our conversation soon turned to an upcoming movie, adapted from a fantasy series that is often denounced for its racism, its sexism, and its Christian subtext. I'm a liberal feminist atheist and she's a lesbian mother of a grammar-school-age boy, so you might imagine that we were united in our condemnation of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

You'd be wrong.

We both adore the Chronicles of Narnia.

In America, many Baby-Boomer and GenX fantasy fans got their life-changing introduction to fantasy with The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. But my introduction was the Chronicles of Narnia. So, while I was happy to see Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings movies, I didn't quite understand the emotional reaction of readers turned on to fantasy by the trilogy. But when, ignorant of Hollywood's plans, I realized a trailer I was watching had to be a movie adaptation of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, this stiff-upper-lip New Englander nearly wept.

The Adaptation

The Chronicles of Narnia were written by C(live) S(taples) Lewis (1898-1963), a member, with Charles Williams and J.R.R. Tolkien, of the Inklings. A Christian apologist and an Oxford and Cambridge don, C.S. Lewis wrote both nonfiction and fiction; some of his works of genre interest are Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories (1966); The Screwtape Letters (1942; as The Screwtape Letters and Screwtape Proposes a Toast, 1961); and the Perelandra trilogy (1938-1945). His most famous series, in and out of genre, is the seven-book Chronicles of Narnia, introduced in 1950 with The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

Published shortly after World War II, the novel had no need for an in-depth explanation of why the four Pevensie children — Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy — were sent away to the country to live with an old professor and his house-keeper. Here at the turn of the millennium, director Andrew Adamson wisely opens LWW with an aerial view of German aircraft dropping bombs onto night-time London. The focus swiftly tightens on the Pevensie family, who are fleeing the explosions. The younger son, Edmund (Skandar Keynes), risks death to retrieve a photograph of his father, who is away at war. This puts Edmund in conflict with the oldest child, Peter (William Moseley), who seeks to provide the missing paternal authority; soon, Edmund is also in rebellion against Susan (Anna Popplewell), who becomes another loco parentis when they must leave their mother behind in London.

They're sent to live with funny-looking old Professor Kirke (a delightful Jim Broadbent), whose immense old house is full of rooms and passages and artifacts that any castle might envy. During a game of hide-and-seek, the youngest child, Lucy (a wonderful Georgie Henley), discovers that not every passage leads to this world. Backing through a wardrobe full of fur coats, she finds herself prickled by pine needles and dusted with falling snow, in a vast wild forest with a glowing gas lamp at its heart. She has entered the world of Narnia.

Here she makes the acquaintance of Mr. Tumnus (an innocent/sinister James McAvoy). A faun, Mr. Tumnus is surprised to meet a Human, a "Daughter of Eve". He reveals that the beautiful winter is a hundred years old ("it's always winter, but never Christmas"), and that this endless season is the product of Narnia's false queen, the White Witch (an icily perfect Tilda Swinton). Mr. Tumnus takes the trusting young girl home for tea, hiding an agenda tied to the White Witch's search for the four Human children who are prophesied to end her rule.

The next Pevensie child to find himself in Narnia is Edmund. The White Witch wins his trust with Turkish Delight, and with the promise that he will be King of Narnia, with his disliked siblings as his servants. But he must lead his brother and sisters to her.

Soon, Edmund denies Narnia and betrays his siblings. Now, the children's and Narnia's only hope of survival may be a mysterious lion, the wise and terrifying Aslan (powerfully voiced by Liam Neeson). But no mortal, Human or otherwise, can predict or control Aslan's movements or actions. You see, he's not a tame Lion....

Too Much Respect?

I never understood the purist fan, who howls in outrage because a remake turns Battlestar Galactica's macho pilot Starbuck into a woman, or because a movie or TV adaptation alters a superhero's origin. After all, what works in a comic-book series or a novel often won't work in a movie. And the original novels, comics, and TV series are still with us, in print and on DVD, so why must an adaptation be identical to the original? But, as the movie adaptation of LWW unfolded, I discovered I was that sort of fan. I didn't want the movie's makers to change a hair of Aslan's mane.

Despite my convulsive kneejerk reactions to every change, the LWW movie is, overall, a faithful adaptation. The novel's subdued allegory is not expanded or made explicit; neither is it eliminated or reduced. Too, Lewis's pagan elements (fauns, Bacchus, animals' worthiness of rescue, etc.) remain intact. Director Adamson gives proper weight to that magical sense-of-wonder scene that stretches from wardrobe to lamppost, as Lucy discovers that she is in another world. With the exception of the not-quite-convincing talking wolves, the CGI effects are fantastic — realistic. And Aslan's redemptive sacrifice remains powerful and moving.

The adaptation's changes (mostly expansions necessitated by the book's brevity) are largely effective. The arrival of Father Christmas (James Cosmo) is successfully recast as a terrifying chase (for the White Witch too travels by reindeer-drawn sleigh). Father Christmas's observation in the novel that "battles are ugly when women fight" has been shorn of its sexism (and thereby made a more accurate observation of the ugliness of combat). Edmund and Peter's expanded conflict provides the movie with the conventional character-development arc that Lewis did not provide (or need to, for the book); and this conflict is not escalated to the point of supplanting Lucy as the central human character.

This is not to say that every change works. Many parents will be disturbed to find that the climactic battle (which Lewis hardly described) has been expanded to fill a fair amount of screen time (but, though LotR-influenced, it doesn't become bloody). Also, halfway through, the director abandons Lewis's use of beautiful white winter as a symbol for evil, substituting barely-lit scenes of war-preparation that are straight out of the LotR adaptations. In interpolating this tired old dark=evil/light=good cliché, and in giving the evil queen a hairstyle (dreadlocks) that is both "black" and a Hollywood villain cliché (cf. Galaxy Quest and the innumerable Predator movies), this twenty-first-century movie adaptation, which is striving to avoid Lewis's twentieth-century prejudices, actually makes Narnia more stereotyped.

Another ill-advised change involves the talking beavers who help the Pevensie children. Lewis gives Mr. and Mrs. Beaver the humorous interactions of an old married couple. The movie pushes this humor to an almost slapstick broadness. It's as if the Beavers (voiced by Ray Winstone and Dawn French) wandered in from Loony Tunes, or from one of the many wiseass talking-animal movies whose previews preceded LWW. The altered Beavers fail to amuse, because their sitcom interactions fight the tone of the movie, and because the change misses Lewis's respect for these characters as good and intelligent creations.

Oddly, my biggest problem with the movie adaptation is that it's a little too respectful. In LWW, his live-action film debut, director Andrew Adamson reins himself in too much. Peter Jackson is equally respectful in his adaptations of LotR, but he's certainly not reined in; he infuses those movies with his enormous unique energy — in a word, his vision. Adamson's LWW adaptation could have used some of the chaotically energetic yet affectionate vision he showed in his animated modern-day classic, Shrek.

The Sins of the Father of Narnia: Should We Now Cast Stones?

I don't love the movie adaptation of LWW. But I like it well, and I recommend it to viewers who can get past its iffy symbology of evil.

If you're discouraged by reports of a Christian subtext in LWW, Lewis always maintained that the Chronicles of Narnia are, in the words of his stepson, Douglas Gresham, "certainly not a Christian allegory." The movie, like the books, works well as straightforward adventure fantasy (which is how I enjoy it).

If, instead, you're (quite reasonably) bothered by the less-than-enlightened views that Lewis or his characters occasionally voiced in the Narnia books, I hope you'll note that Lewis died, in his sixties, in 1963. A white man born in 1898 would not hold turn-of-the-millennium views, and while Lewis's anti-egalitarian beliefs shouldn't be supported or condoned, there's no use flogging a long-dead author for being a product of his time.

I must confess, I find the flogging ironic, because in the Narnia books, this supposedly backwards man created female heroes (not all white) and female villains who are more active, more numerous, more believable, and more in control of their own destinies than the so-called heroines and villainesses of all too many recent fantasy/SF movies and books. And, to its credit, the movie adaptation of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe leaves its strong female characters strong. An adaptation that is too respectful retains the original's good points.