|

Interview Thread

<< | >>

| FEBRUARY ISSUE |

-

-

-

Turtledove Interview

-

-

-

-

February Issue Thread

<< | >>

-

Mailing Date:

30 January 2003

|

| LOCUS MAGAZINE |

Indexes to the Magazine:

|

| |

|

|

|

|

THE MAGAZINE OF THE SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY FIELD

|  |

|

|

|

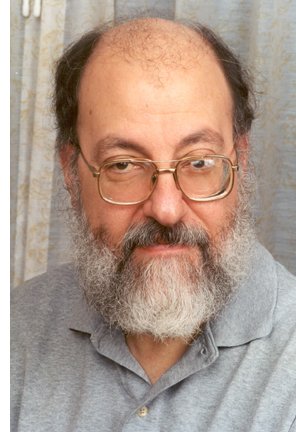

Harry Turtledove: Revisioning History |

February 2003 |

|

A prolific and popular writer of alternate history novels, Harry Turtledove was inspired to study Byzantine history after reading L. Sprague de Camp's 1941 novel Lest Darkness Fall, and eventually earned a Ph.D. in that subject from UCLA. Early works, including first novel Wereblood (1979; uncharacteristically, a sword & sorcery novel) appeared under the name "Eric G. Iverson". Turtledove's long running "Videssos" cycle, about Romans transported to another universe, began in 1987 with The Misplaced Legion. Among many works since then are Agent of Byzantium (1987), US Civil War novels The Guns of the South (1992) and How Few Remain (1997), a series about aliens who interrupt World War II beginning with In the Balance (1994), and Ruled Britannia (1992), about a Britain conquered by the Spanish Armada. His short fiction includes the Hugo Award winning novella "Down in the Bottomlands" (1993), Hugo and Nebula nominee "Must and Shall" (1995), and Hugo nominee "Forty, Counting Down" (1999). The Harry Turtledove Website, maintained by Steve H Silver, catalogues the author's many works.

|

Photo by Beth Gwinn

|

Excerpts from the interview:

“Historical fiction and science fiction both do one essential thing the same way: they’re both building a created world different from the world in which we normally live. They both sprang from the same impulse: that the world around us is changing and being changed by technology. Historical fiction originates in the early 19th century (Sir Walter Scott), and this is the first time technology and the way people lived were changing rapidly enough to be perceptible in the space of a lifetime. Before that, you didn’t really have the sense that your grandfather or your father, or even you as a young person, lived a different life from the way you did as an adult. In medieval times they painted the Crucifixion with Roman soldiers dressed in medieval armor and saw no incongruity in it because they just assumed that everything was always like the way it was at their particular moment.”

*

“Real historians have discovered alternate history — although they don’t call it that; they call it ‘counterfactuals.’ I find those mostly uninteresting, because they do the same thing novels do except they don’t have to bother with characterization. It’s similar to game fiction. Alternate history in game fiction bears the same relationship to character-driven alternate history that technothrillers do to SF — more concerned with the background and the gadgets than with the effect of the changes on society. To me, the best and most interesting way to portray changes is to make the characters as interesting as possible. You have to work very hard to try to figure out how they would think under those changed circumstances and to present that to the readers in a way they find interesting and believable.”

*

“I did homework on Ruled Britannia for six years before I started writing it, because I did not think I could do it as well as I wanted to. It’s like writing about the Civil War — you’ve got to be just about word perfect, or else it’s going to go down like a lead balloon. Although our Civil War is massively uninteresting to most of the rest of the world. You cannot sell translation rights to American Civil War stories overseas. It’s not their history. Europe doesn’t care. They’ve had much more and much worse history to worry about — they don’t care about this little dust-up that we had!”

“I did homework on Ruled Britannia for six years before I started writing it, because I did not think I could do it as well as I wanted to. It’s like writing about the Civil War — you’ve got to be just about word perfect, or else it’s going to go down like a lead balloon. Although our Civil War is massively uninteresting to most of the rest of the world. You cannot sell translation rights to American Civil War stories overseas. It’s not their history. Europe doesn’t care. They’ve had much more and much worse history to worry about — they don’t care about this little dust-up that we had!”

*

“We are more introspective than we used to be. Christianity and Islam have imposed a different kind of conscience on us. Aggressive displays of ego were the cultural norm in Greece and Rome. You were your front much more than you are nowadays. We seem to be darker on the inside than we had been. There’s something in us that needs to be dissatisfied. I get hassled because my characters generally behave in a reasonable, rational way. Well, I try to be a reasonable, rational person. Of course it doesn’t work all the time — it can’t. But I come from that de Campian, Andersonian vein: ‘Here’s what we do. Here’s how we try to fix it.’ I see people who write characters who are loonies and make them convincing and believable, and I envy them tremendously. I don’t really understand them. It’s funny, because I’ve created my own monster. In the ‘Great War’ and ‘American Empire’ books, I’m writing the person who is the functional equivalent of Adolf Hitler. I’m inside his head — and that’s a very strange place for somebody who thinks of himself as a fairly rational fellow to be. That’s alarming.”

The full interview, with biographical profile, is published in the February 2003 issue of Locus Magazine.

|

|

|

|