|

B

R I A N

A

L D I S S : Young Turk to Grand Master

(excerpted from Locus Magazine, August 2000) | ||

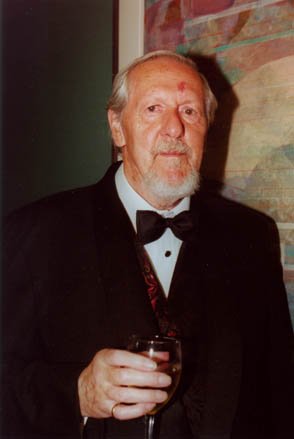

Photo by Beth Gwinn |

Brian W. Aldiss was born August 18, 1925 in East Dereham, Norfolk, England. He served in the Royal Signals in Burma and Sumatra until 1947, worked as a bookseller in Oxford until 1956, and in the same year became a full-time writer. He is the father of four grown children, two with first wife Olive (née Fortescue; married 1948, divorced 1965), and two with second wife Margaret (née Manson), whom he married in 1965. She died in 1997. Aldissís first SF sale was ëëCriminal Recordíí (Science Fantasy 1954). His first SF novel, Non-Stop (1958; US title Starship) has become a classic in the field. He won a 1962 short-fiction Hugo for the novelettes which became The Long Afternoon of Earth (1962; UK expanded as Hothouse). In the later 1960s he became known as a British New Waver, publishing works like French Surrealist-inspired novel Report on Probability A (written in 1962 but not published until 1968) and the ëëAcid-Head Waríí stories, a mixture of the Joycean and the psychedelic, gathered in Barefoot in the Head (1969). His novella ëëThe Saliva Treeíí (1965) won him a Nebula with its striking combination of influences -- H.G. Wells and H.P. Lovecraft. Among many later works were the non-SF, semi-autobiographical trilogy The Hand-Reared Boy (1970), A Soldier Erect (1971), and A Rude Awakening (1978); the lyrical fantasy The Malacia Tapestry (1976); and the ambitious SF ëëHelliconia Trilogyíí: Campbell-winner Helliconia Spring (1982), followed by Helliconia Summer (1983) and Helliconia Winter (1985). |

|

§ Amazon links: Amazon UK links:

§

Search Amazon.com for

Search Amazon UK for § |

As editor, Aldiss co-edited with Harry Harrison a series of Best SF annual volumes (1968-1976). He published history of SF Billion Year Spree in 1973, famously claiming Mary Shelleyís Frankenstein as the first SF novel; a revised and expanded version with collaborator David Wingrove, Trillion Year Spree (1986) went on to win a Hugo. His speculations on genre origins also appeared in novels Frankenstein Unbound (1973) and its sequel Dracula Unbound (1991). His most recent novel is White Mars (1999), in collaboration with physicist Roger Penrose. Aldiss has also been active in SF leadership roles for many years, as president of British SF Association (1960-1965) and World SF (1975-1979), co-founder of the Campbell Memorial Award, and other significant roles. He has been Guest of Honor at a number of SF cons including two Worldcons, is a yearly guest at the International Conference on the Fantastic in Florida, and has just been named an SFWA Grand Master.

ëëIím lucky that SFWA has such a short memory. I was always the Young Turk, the gadfly. Part of the New Wave, although I didnít fit in there either! I spent years, and two histories, putting the so-called Old Guard in their place, and now Iím one of them! ëëIím still trying to come to terms with being named a Grand Master, just like Robert Heinlein. I just canít believe it. But thereís really, when you think about it, less contrast between me and Heinlein than might seem apparent. After all, that first novel of mine, Non-Stop, is directly attributable to Heinlein. His ëCommon Senseí seemed to me such a good story, but bereft of any human feelings. I thought long about that story, and then I thought how wonderful it would be to write about a spaceship in which people have been imprisoned for generations and to put in something of the human feeling. So that novel is directly attributable to Heinlein. I thought, in my youthful arrogance, that I could do it better -- I didnít! I thought I could do it differently, and I think I did do it differently. And I suppose that on the whole, Iíve concentrated on doing things differently ever since. ëëFor my latest novel, I wouldnít say it made me mad, but what made me very worried was this assumption that when men get to Mars, theyíre going to behave as theyíve done all over the planet Earth -- terraform it, and turn it into a second-rate imitation of Earth. ... Thereís a lot to the old saying, ëWishing makes it so,í and I thought a counter- argument should be put up to this idea of terraforming. So thatís what I did in White Mars. Ö Itís long been a hypothesis of science fiction, that humanity is about change. Well, letís hope the change is for the better. It might be. Whereas if you were stuck on Mars, you would see things very differently. ëëThatís the thesis of the book. And Iím very proud and pleased to have written it. As for my collaborator, Roger Penrose, this is a way in which my life has become engulfed in amazing circumstances. My wife Margaret and I sold our house to Sir Roger Penrose and his wife. Roger Penrose is basically a mathematician. He held a position at the Mathematical Institute in Oxford, but also heís so multi-talented, so curious, such a quick brain, that heís mastered a number of other fields. Cosmology, for instance. And then this glorious subject of human consciousness. Talking to Roger, I found we both agreed that AI, as they call it, is not going to be achieved by present-day machines. ëArtificial Intelligenceí -- that makes it sound simple, but what youíre really talking about is artificial consciousness, AC. And I donít think thereís any way we can achieve artificial consciousness, at least until weíve understood the sources of our own consciousness. I believe consciousness is a mind/body creation, literally interwoven with the body and the bodyís support systems. Well, you donít get that sort of thing with a robot. ëëWe had that agreement, and then we started to talk. I didnít understand a lot of Rogerís theories. Iím just not trained to do it. But he encouraged me by saying, ëThere was a time when I thought Iíd like to be a science fiction writer.í So I gave him the chance. Margaret and I had dined with Roger and his wife in college, got to bed rather late, and at four in the morning I woke up from a wonderful dream. It was a dream about the planet Mars. I sat up in bed, absolutely stunned by this whole creative dream. Margaret said, ëYouíll remember it in the morning. Go to sleep now.í But I feared that I wouldnít. I crept downstairs and I did a five-page synopsis. That dream was very much the basis of the book. And when Iíd done it, I thought, ëIíll send this to Roger. Perhaps heíd like to collaborate.í Which he did, wholeheartedly. I canít help believing that these things that come from the subconscious mind have a sort of truth to them. It may not be a scientific truth, but itís psychological truth. And in that respect, I believe thereís a psychological truth in White Mars. If youíre stuck on that planet, youíll either cooperate or youíll die." * ëëLetís talk about ëSuper-Toys Last All Summer Longí. A friend well known in British science fiction circles, Dr. Chris Evans, who works at the National Physical Laboratory, was given the chance to edit an issue of Harperís Bazaar for Christmas of 1969. He said, ëCome on, Brian, we must have a story of yours in there.í So I wrote ëSuper-Toys....í Itís about another populated world where you have to get permission to have children, so thereís a thriving industry of small android kids -- child substitutes. David is introduced to this family and is programmed not to know heís an android. So a lot of the pathos of this story lies in the fact that David thinks heís a perfect little boy, but his ëmotherí just cannot accept him. She doesnít love him, and however he tries to please, he doesnít please. ëëThis story seemed to be quite popular; it was well received by the Harperís readers. But after all, a story.... You put it into a collection, you lose interest, and perhaps everyone loses interest in it. But, when I knew Stanley Kubrick, thatís the story he wanted to buy, and he was obsessive about it. I didnít want to sell it, but eventually he persuaded me. He said he couldnít think about it until he bought it, but after he bought it he still couldnít find the story for it. I believe that actually his tactics were mistaken, because what Kubrick wanted was another big space opera. I said to him, ëYou know, Stanley, you canít do it with this story.í He said, ëWhy not? I did it with Arthur Clarkeís ëThe Sentinelí. Itís the same length, 2000 words.í And he maintained it was easier to turn a short story into a movie than to condense a novel into a movie. (I guess he had that trouble with Barry Lyndon.) But ëThe Sentinelí is essentially outwardly directed, and ëSuper-Toysí is inwardly directed. ëëEventually things fell apart, and I went back to living my own life instead of living Stanleyís life, which was a great relief! I had 30 years of independent existence. He was a difficult man. The pure genius is not an ordinary man. But then you must ask yourself eventually, ëWhy did Stanley so like that story?í I believe it touched an emotional chord in him. Perhaps he had also been a small boy who could not please his mother, whatever he did. If you extend that, you realize thatís probably why I wrote the story, although I never thought of it at the time. But whatever I did as a small boy, I could never please my mother. So that was the emotional basis of this somewhat intellectual story. ëëYears went by, and Stanley Kubrick died. Steven Spielberg took over his effects, so then I started thinking about my story again and wondering if I could get it back into my possession. But turning up the contract, I found that the phrase ëin perpetuityí occurred an undesirable number of times. Then, thinking more about the story, I thought, ëWhy donít I continue this? Itís very interesting. What happens next to David?í So I wrote another story, ëSuper-Toys When Winter Comesí. ëëThis is another of lifeís coincidences. Iíd finished it and printed out the story, and I got a phone call from Jan Harlan, Kubrickís brother-in-law. (Stanley married his sister.) A very nice guy. He was a business manager and also a producer on a lot of Stanleyís films. He wanted to come over and see me because heís making a documentary, not only about Kubrickís life but about how his influence goes into the future. I seemed to be an important element in that, at least in Janís mind. So I showed him this story Iíd just written, because by now Spielberg had taken over the original story, and announced he was going to film AI, which was a development of ëSuper-Toys....í Jan said, ëIíll send this to Spielberg. Maybe heíll like it.í (Thereís obviously a great advantage in having a producer receive a story through a friend rather than from a stranger.) Spielberg said he was interested, and he wanted the story. ëëThen I thought more about it, and I wrote to Steven and gave a suggestion of how the story should go on. He got in touch with Jan Harlan, saying, ëThereís one sentence in Aldissís letter that I really like and would love to buy.í I was charmed by the idea of selling one sentence for quite a good little bundle of money -- more than Iíd get as an advance for a novel! But then, for once my business sense revived, and I thought, ëHey! What am I doing selling him one sentence? Why donít I write a third ëSuper-Toysí story incorporating the idea of that sentence? That I did, and again I sent it to Jan. Jan sent it to Spielberg, and Spielberg then bought the two further stories. Which is not, of course, to say that heís going to make a movie of them. But one always hopes that oneís material might be transformed more or less unchanged to the screen. ëëIn this case, the cards are down. Spielberg has guaranteed that he will make AI as Stanley wanted it, with climatic change -- New York flooded a bit deeper than today. But at least there should be a card saying the idea came from my short stories. Kubrick was obsessed by Pinocchio. He wanted David to become a real boy. I thought that was skyfire -- I didnít think that was science fiction. I donít know what you think of my career; I donít know what I think of it myself. But Iím certainly the only guy that sold short stories to both Kubrick and Spielberg! So that thought pleases me. Warms the dying embers." * ëëWhy do so many people dislike science fiction? The answer goes like this: You have to think of science fiction in contrast to its nearest competitor, heroic fantasy. In heroic fantasy, by and large, things are pretty stable, and then some terrible evil comes along thatís going to take over the world. People have to fight it. In the end they win, of course, so the earth is restored to what it was. The status quo comes back. Science fictionís quite different. With science fiction, the worldís in some sort of a state, and something awful happens. It may not be evil, it may be good or neutral, just an accident. Whatever they do in the novel, at the end the world is changed forever. Thatís the difference between the two genres -- and itís an almighty difference! And the truth is science fiction, because we all live in a world thatís changed forever. Itís never going to go back to what it was in the í60s or the í70s or the í30s, or whatever. Itís changed. ëëI think of heroic fantasy as having usurped much of the position of science fiction. In the glory days of the í60s, I remember the time when suddenly the science fiction section of the bookshop was moved right up to the front door. It was extraordinary. From nowhere, it leapt into prominence and into some sort of intellectual acceptance. Now, of course, SF has faded away, and itís in the background again. However, itís become a part of general life now. When I went to see The Truman Show at the local cinema, I looked around and the audience was absolutely engrossed in this thing, and none of them knew they were actually watching science fiction." |

| © 2000 by Locus Publications. All rights reserved. |