|

N

E I L

G

A I M A N : Of Monsters & Miracles (excerpted from Locus Magazine, April 1999) | |||

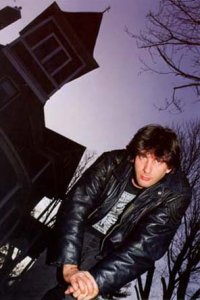

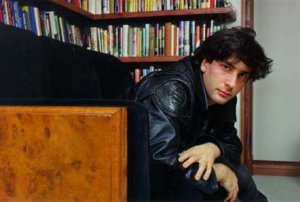

Photos by Beth Gwinn |

Neil Richard Gaiman, born in 1960, was a freelance journalist in the early ’80s. His first major project in the field was co-editing (with Kim Newman) Ghastly Beyond Belief (1985), the anthology of unintentionally hilarious British pulp genre fiction. He also wrote the reference book Don’t Panic: The Official Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Companion (1988). His long career in graphic novels began with Violent Cases (1987), the first of many notable collaborations with artist Dave McKean. Gaiman as graphic novelist (comics text writer) is best known now for the Sandman series, which originated in 1989 and continued for many episodes and volumes, including A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1990) with art by Charles Vess, which received a 1991 World Fantasy Award for Best Short Story - the first (and only) time a comic won that prize. Gaiman, on his own, has been nominated for two other World Fantasy Awards. He wrote a number of other graphic novels, plus a graphic children’s book with Dave McKean, The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish (1997). Gaiman’s entry into novel-writing came as co-author, with Terry Pratchett, of humorous fantasy Good Omens (1990). Next came Neverwhere (1996), which was also a serial for BBC television. His newest work, Stardust, exists in two versions - an illustrated one with artwork by Charles Vess (1998) and text-only (1999). Gaiman’s short fiction, poetry, and miscellany were collected in Angels & Visitations (1993). A revised, expanded collection, Smoke and Mirrors, appeared in 1998. He married Mary McGrath in 1985; they have a son and two daughters. In 1992, the family moved to the US, where they make their home in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

''One of the things I loved about first moving to the States was feeling like an alien - a legal alien. And I loved the strangeness of everything, the weird discontinuity. I loved just the fact that you people drive on the wrong side of the road, and all your stamps look different. I like that because it makes me feel just a little uncomfortable. In many ways, some of the charm of both Neverwhere and Stardust is the fact that, while both are very English fiction, they were both created by an expatriate Englishman. Nostalgia’s the wrong word, but it’s almost as if one is recreating England in one’s head, seeing it from a long way away and picking those elements one likes. ''I was thrilled when John Clute reviewed Neverwhere and said it contained the bones of the best London novel yet. If I did anything good in Neverwhere - which I’m still not entirely satisfied with - creating a sort of mythic London was in many ways much easier, writing it in places like a hotel room in Galveston, Texas or sitting around at home in Minneapolis. One could isolate why one wanted to make it mythic, what one was going for. And I love it when people come up to me at signings and say, ‘I just got back from London. Before I went, I read Neverwhere, and we stayed in Earl’s Court and we got to go to Knightsbridge,’ and it’s as if these places are actually taking on a mythic dimension for them. ''I started writing, sent stories out, got rejection slips back. Then got up one morning, went, ‘You know what? I think I’m doing this wrong. I’m going to go find out how the world works.’ And became a freelance journalist. This was around ’81, ’82. I did it simply by getting up one morning and being a journalist. It seemed the easiest way to do it. I got my first job by lying about who I’d written for, listing all the magazines I’d like to write for, and over the next five years, I actually did write for all those magazines - so I didn’t lie, I was just a little mixed up in my chronology! I wrote about SF. ''Stardust has one brief moment of almost Tarantino-esque violence, a couple of gentle sex scenes, and the word ‘fuck’ printed very, very small once. But apart from that, it could have been written in 1920. The magic of writing, those things we do to convince ourselves we’re doing it the right way. Up until 1986, I wrote everything on a typewriter. From 1986, when I bought my first computer, I did everything on that, except maybe one short story handwritten. Then it came to Stardust and I thought, ‘OK, I want to write this in 1920.’ I went out and bought a fountain pen - curiously enough, the fountain pen I’m signing the book with, which has a lovely sort of arc of closure to it, a feeling of completeness. And I bought some big, leatherbound blank volumes, and I sat and wrote Stardust. ''I think it really changed the way I wrote it. You think about the sentence more before you write it. On a computer, it’s almost like throwing down a blob of clay and then molding it a bit. But I can’t do that with a fountain pen, so I think about it a little more. And I wanted a first and second draft, which is again something that seems to be fading. A couple of years ago, when I was editing The Sandman: Book of Dreams, I noticed that what 10 years earlier would have been 3,000-word short stories were coming in at over 6,000 words. And it was as if people writing them on computers let them bloat. If you have a choice between two things, you do both of them. With Stardust, I wanted to go back to the thing I was taught when I started writing short stories: Write them as if you’re paying them by the word. It’s 60,000 words, which is what books used to be. Obviously, the book has certain drawbacks and disadvantages. You can’t use it as a doorstop. You probably couldn’t seriously injure a burglar with it, and a stack of falling Stardust will not kill anybody. ''Stardust is very intentionally a fairy tale, but I didn’t want to set it in a sort of never-never historical period. It’s very solidly set in Victorian England, actually in a period after fairy tales were done with, but it’s a fantasy in the tradition of Dunsany or Hope Mirrlees, whose classic novel Lud-in-the-Mist is still one of my favorite books. And C.S. Lewis. There may be a little bit of James Branch Cabell in there too, a few Cabell riffs, although what I tended to do was try and go back afterwards and humanize them in a way Cabell never did, he had such a jaundiced view of humanity. ''The other joy of writing Stardust was writing a book in which the readers know more than the main characters, in which various plot strands converge in various ways, and many of them miss each other in ways that are deeply satisfying for the readers and would be amazingly frustrating if you watched them happen in a film. It was nice to think about something just purely in a novelistic way, having hopped as I have from medium to medium. ‘This is a book. These are words.’ ''I’m about to start a novel set in America. I’d been mulling over elements of it for two or three years. And then, when I was in Iceland on my way to a sort of micro Scandinavian tour of Norway, Denmark, and Finland, wandering around Reykjavik in a very sleep-deprived state in summer when the sun never sets, all of a sudden the American novel came into focus. It was like I had enough distance from America to see, ‘It’s going to be an urban fantasy set in America, all about the things I think and feel and wonder about America, having been here for six years.’ Trying to create an America that’s much more real than the magic America I wrote about in Sandman. ''I knew so much more about America before I came here! I remember initially assuming there was an awful lot underneath the surface, then living here for a little while and thinking, ‘Oh, there’s nothing underneath the surface - what you see is what you get.’ And then, coming through that and deciding, ‘Yeah, there actually is an awful lot under the surface, but it’s not what I was looking for.’ England has history; Americans have geography. Which goes back to that joke, ‘America is a country where 100 years is a long time, and England is a country where 100 miles is a long way.’ Both of those things are true on many levels. There really isn’t a great English road trip tradition, because in three or four days, you’ve done it all. Whereas in America, the idea of the road trip is this magnificent long slog. ''This next novel has a working title of American Gods. It’s urban, it’s a road trip, and it’s got gods in it. It’s going to have a certain amount of horror, but I don’t want it to be a horror novel. I don’t actually think I could write a horror novel. Horror is something I like to use as a condiment, a spice. You can use it to add tang to what you’re doing. But an entire dish of it.... Also, from just a cruelty-to-writers point of view, I don’t like to go to that place day after day, week after week, month after month. This is a book that will have its fair share of zombies, but also its fair share of gods. ''In Castle of Days, Gene Wolfe had a line I really remember responding to. He defined good literature for somebody, and said (and I’m quoting from memory) it was literature that could be read with pleasure by an educated reader, and reread with increased pleasure. And that was what I was always going for in Sandman: the idea that you could read it once for the story, and if you go back and read it again, you’ll get all of this cool nuance and interplay and stuff that you missed the first time, which will make it even better. And then when you’ve read the whole story, Sandman volumes 1 through 10, you can start again at the beginning, and the shape of events will change, and what they mean will be different from reading it through the first time. Even with something like Stardust, I tried to do that. ''Other future projects right now? There’s a children’s book called Coraline which I’m doing for Avon children’s books. I hope it will be illustrated, but it’s not going to be an illustrated book in the way that The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish was. But I’m also going to do another illustrated book with Dave McKean which will be like that, called The Wolves in the Walls, about a little girl who is convinced that the scratching she hears in the walls of her house is from wolves. It’s the story of how the family gets their house back and reclaims it from the wolves who take over. ''I’ve been working on the movie of Neverwhere with Jim Henson Productions. But the coolest thing I did this past summer was write the English script for a Japanese film, Princess Mononoke-Hime. I don’t know what the English title will be when it gets released here, but it’s an animated film made in Japan which is going to be released into cinema. My job was to take the literal Japanese translation and turn it into lines of dialog that didn’t sound like Saturday morning animation. It’s astonishing, like Star Wars set in a 14th-century Japanese forest. ''I’m not a novelist any more than I was a comics writer or a TV writer. I’m a storyteller. I feel vaguely like I’m getting away with something in doing this. I’m still worried that one day they’ll come and take it all away from me. Look, I get to make things up for a living! When you’re a little kid and you make things up, they say, ‘Don’t make things up.’ And then they say, in even more warning tones, ‘You know what will happen if you make things up.’ And then they don’t tell you. As far as I can see, it involves a lot of international travel, huge crowds of appreciative people who turn up to thank you and get their books signed, and being #1 on the next Locus Bestseller List. So now you know what happens if you make things up!’’ |

||

| © 1999 by Locus Publications. All rights reserved. |